- Clinical Technology

- Adult Immunization

- Hepatology

- Pediatric Immunization

- Screening

- Psychiatry

- Allergy

- Women's Health

- Cardiology

- Pediatrics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology

- Pain Management

- Gastroenterology

- Infectious Disease

- Obesity Medicine

- Rheumatology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Pulmonology

Oropharyngeal candidiasis: Diagnostic clues, treatment tips

The most common manifestation of oropharyngealcandidiasis (OPC) is pseudomembranous candidiasis, commonlyknown as "thrush," which appears as a whitish yellow,curdlike discharge on the mucosal surfaces. Other forms ofOPC include denture stomatitis, angular cheilitis, and glossitis.Patients with denture stomatitis are usually asymptomatic, butthe tissue beneath the denture is typically red and hyperplastic.Patients with angular cheilitis may complain of a burning sensationat the margins of the lips. Candidiasis involving thetongue can be exuberant and is usually associated with complaintsof a white tongue, taste alterations, and a burning sensationof the tongue. The diagnosis of OPC can be establishedby identifying typical fungal elements on potassium hydroxidepreparation or Gram stain of scraped material. Treatment optionsinclude clotrimazole, fluconazole, itraconazole, and nystatin.(J Respir Dis. 2008;29(3):128-135)

ABSTRACT: The most common manifestation of oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC) is pseudomembranous candidiasis, commonly known as "thrush," which appears as a whitish yellow, curdlike discharge on the mucosal surfaces. Other forms of OPC include denture stomatitis, angular cheilitis, and glossitis. Patients with denture stomatitis are usually asymptomatic, but the tissue beneath the denture is typically red and hyperplastic. Patients with angular cheilitis may complain of a burning sensation at the margins of the lips. Candidiasis involving the tongue can be exuberant and is usually associated with complaints of a white tongue, taste alterations, and a burning sensation of the tongue. The diagnosis of OPC can be established by identifying typical fungal elements on potassium hydroxide preparation or Gram stain of scraped material. Treatment options include clotrimazole, fluconazole, itraconazole, and nystatin. (J Respir Dis. 2008;29(3):128-135)

Oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC) is a common clinical problem caused by fungi of the genus Candida, of which Candida albicans is the most commonly encountered species. OPC refers to disease caused by this fungus in or adjacent to the mouth. Occasionally, OPC is associated with esophageal candidiasis.

The presence of OPC should alert the physician to look for an underlying disease that may predispose the patient to this fungal infection. Two significant underlying problems associated with OPC that are frequently encountered are HIV-1 infection and neutropenia secondary to myelodysplastic disorders or cancer chemotherapy.

In this article, we will describe the common clinical presentations of OPC and review diagnosis and treatment. We also will briefly discuss the pathophysiology of OPC.

THE CAUSATIVE MICROORGANISM

C albicans, the predominant cause of OPC, lives in small numbers on the mucous membranes (the oropharynx, GI tract, and vagina) of humans and other vertebrates. The fungus survives within a dynamic consortium of resident microorganisms. It can be cultured from normal mouth tissue in many adults.1

C albicans has several morphologies, all of which can be seen in the lesions of OPC: yeast cells; true hyphae, which are cylindrical; and pseudohyphae, which are chains of elongated spheroidal cells. Another Candida species occasionally associated with OPC, particularly in patients with HIV infection, is Candida dubliniensis. C albicans adheres to mucous epithelia through fungal adhesins that are covalently anchored to the fungal cell walls. These adhesins have additional functions: they aggregate the fungus to form the characteristic mats and colonies that characterize pseudomembranous OPC. The Als adhesins bind nonspecifically to many peptide structures through low specificity protein-ligand interactions2 and perhaps through amyloid-like interactions as well.3

The hyphae-specific adhesin, Hwp1p, is a substrate for epithelial cell transglutaminase, which covalently cross-links the fungus to buccal epithelial cells.4 Therefore, many interactions result in a tightly adherent biofilm of Candida cells on mucous membranes when the fungus proliferates in the disease state.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

OPC occurs most often in persons with some identifiable defect in host defenses; almost always, the defect is acquired. The following 2 case histories illustrate common features of OPC.

Case 1

A 24-year-old graduate student came to the office complaining of "white sores in my mouth and pain when I swallow." He was homosexual and last had sexual intercourse 2 months ago, unprotected. He had had fevers and swollen lymph nodes for the past 2 weeks.

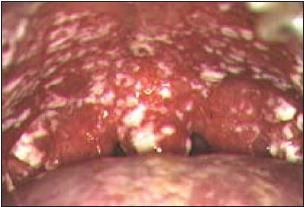

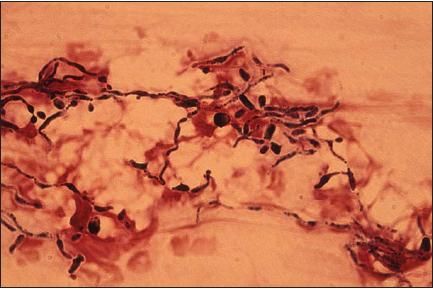

On physical examination, he had a temperature of 38.1°C (100.6°F); generalized lymphadenopathy; and chalky-white, raised, circular lesions on the soft and hard palate (Figure 1). Scraping the lesions with a tongue blade resulted in slight bleeding from beneath the lesion. Gram stain of the material showed Gram-positive yeasts and pseudohyphae (Figure 2).

Figure 1 – Pseudomembranous candidiasis is the most common presentation of oropharyngeal candidiasis. Note the numerous curdlike lesions on the soft and hard palate.

Figure 2 – Gram-positive (blue-black) yeast cells and filamentous forms of the fungus are seen in this Gram stain. The patient had pseudomembranous candidiasis.

Comment: This young man had pseudomembranous candidiasis, commonly known as "thrush," the most common form of OPC. He had the acute retroviral syndrome caused by recent infection with HIV, which is often accompanied by transient, marked reduction in circulating CD4+ cells. Adequate numbers of CD4+ cells are crucial for maintenance of normal host defense on mucous membranes. The patient was given oral fluconazole, 100 mg/d, for 7 days. The lesions disappeared within 2 days; there had been no recurrence 2 months later.

Case 2

A 54-year-old man complained that when he removed his upper denture plate, the tissue beneath the plate was intensely red and he had a slight burning sensation on his hard palate.

Comment: This is typical denture stomatitis, which is almost always associated with and exacerbated by candidiasis. Topical or oral antifungal medications usually control the infection.5 Vigorous cleaning of dentures is recommended to remove the Candida biofilm.

Discussion

These 2 cases demonstrate different predisposing causes of OPC-decreased cell-mediated immunity and the presence of an oral prosthesis, respectively. Both are common settings in which C albicans may cause disease.

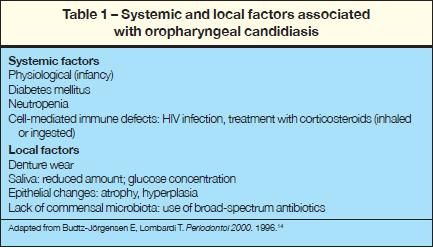

Systemic and local factors influence whether OPC develops in a particular person (Table 1). OPC frequently occurs in patients with neutropenia. These patients often have other predisposing risk factors for OPC, such as broad-spectrum antibiotic use. In the setting of neutropenia, esophageal candidiasis is an ominous finding; there is a risk of vascular invasion, since functional neutrophils are required to prevent penetration of Candida species beyond the epithelial basement membrane.6 However, penetration of fungi deep into underlying tissue and disseminating to other organs is not believed to occur in OPC.

Use of corticosteroid inhalers is occasionally accompanied by OPC in the sublingual area, where cell-mediated immunity is reduced in the presence of high concentrations of corticosteroids. The risk can be reduced if patients rinse their mouths after using their inhalers.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics transiently eliminate or change the normal microbiota of the buccal membranes and may lead to overgrowth of C albicans. This occurs frequently in infants and occasionally in adults with diabetes, and it often occurs in HIV-infected patients who have moderate reduction in cell-mediated immunity.

OPC is the most common opportunistic infection in HIV-infected patients because of the reduction in the total CD4 count. It occurs occasionally in HIV-infected patients who have esophageal candidiasis, but the esophageal disease does not predispose them to vascular invasion as it does in neutropenic patients.

Prosthetic devices, such as dentures, that distort the oropharyngeal anatomy and change the local environment predispose persons to OPC.5 Malfitting dentures may be associated with angular cheilitis, or perlche. Reduced amounts of or absent saliva (xerostomia) is a risk factor for OPC. Saliva contains a considerable number of important antifungal components, such as defensins, histatins, lysozyme, and lactoferrin; thus, adequate saliva is necessary.

SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

One authority lists more than 10 different presentations of OPC, both acute and chronic.7 We will discuss some of the more common and easily recognizable forms. As mentioned above, the most common manifestation of OPC is pseudomembranous candidiasis. Less common forms include lesions on the tongue; red, hyperplastic tissue beneath a maxillary denture; and angular cheilitis. With experience, the diagnosis can be made reliably by visual observation alone. Nevertheless, it is easy to confuse OPC with other oral lesions, such as hairy leukoplakia and hairy tongue.

Pseudomembranous candidiasis is easily recognized on visual inspection of the oropharynx. It appears as a whitish yellow, thick curdlike discharge on the mucosa. Patients typically complain of pain on swallowing liquids and solids. Occasionally, patients who have long-standing disease (associated with HIV infection and low CD4 counts) have few complaints despite extensive disease. Odynophagia perceived in the chest is usually a good indicator of the presence of esophageal disease, which may be the first AIDS-defining opportunistic infection.

Denture stomatitis is almost always asymptomatic.5 The characteristic signs are chronic erythema and edema of the area of the palate that comes in contact with the dentures. Patients with angular cheilitis may complain of a burning sensation at the margins of the lips. They may also complain of the moist material at the lip margins. This is seen usually in conjunction with malfitting dentures, which alter the bite.

Candidiasis involving the tongue (glossitis) can be exuberant and is usually associated with complaints of a white tongue, taste alterations, and a burning sensation of the tongue.

MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

Given a compatible history, an experienced clinician can make the diagnosis of pseudomembranous candidiasis by visual inspection of the buccal mucosa. When the diagnosis is in doubt, taking a scraping from the lesion and Gram staining the material is often diagnostic.

Scrapings of the lesions beneath dentures or in areas of angular cheilitis may be difficult to interpret. Both of these types of lesions are characterized by vigorous host responses, which may obscure the underlying fungal cause. The diagnosis is made by obtaining a compatible history, such as the presence of a dental plate or malfitting dentures in a patient with angular cheilitis, and a diagnostic Gram stain.

Candida species are easily recognized on Gram stain or 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation of specimens. Candida species are Gram-positive or Gram-variable on staining; the latter denotes that crystal violet stipples the surface of the fungus rather than uniformly staining it. Similarly, all morphologies of the fungus are readily seen on KOH preparation. Gram stain has the advantage of providing a permanent record as well as highlighting the fungus from the surrounding background material, although it requires more preparation time.

Gram stain of the curdlike lesions on buccal membranes demonstrates a tangle of oral bacteria, proliferating fungus (predominantly yeast cells and pseudohyphae), and polymorphonuclear leukocytes on an eosinophilic background (Figure 2). The role of coaggregated bacteria (mostly Gram-positive) is unknown, but may be important.

Candida grows rapidly on most common culture media used for bacteria or fungi in the medical microbiology laboratory. However, it is not good practice to rely on culture for the diagnosis of OPC, since the fungus is part of the normal microbiota and, thus, may be cultured from persons who are healthy. Culture of the microorganism is not necessary for the diagnosis and should be reserved for troublesome, recurrent OPC in which the causative Candida species may be resistant to drug therapy.

TREATMENT

The objective of treatment is to eliminate the signs and symptoms of the disease and to prevent recurrence.8 Adequate cell-mediated immunity is a requisite for the prevention of OPC.9 When cell-mediated immunity is reduced, recurrences may be frequent.

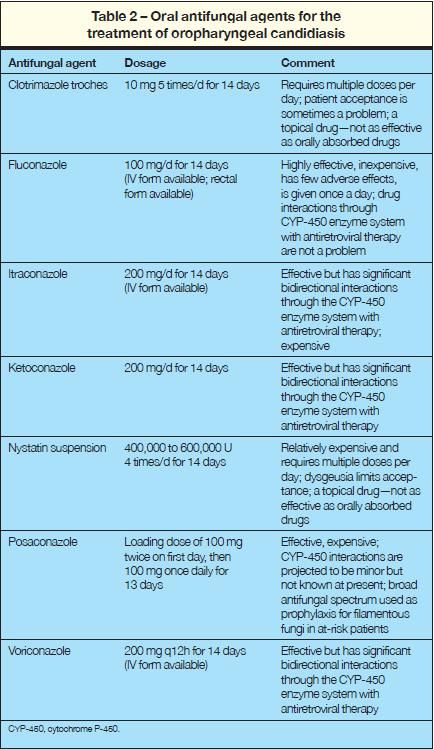

Table 2 lists the oral drugs useful for the treatment of OPC. Fluconazole is the standard by which other antifungal drugs are measured in the treatment of OPC, with respect to efficacy, lack of toxicity, ease of administration, and low cost. A 7- to 14-day course of fluconazole, 100 mg/d, is usually adequate.8 A recurrence in less than 3 weeks is uncommon even when an underlying host defense defect is still present.

Orally absorbed azoles, such as fluconazole, are very effective as prophylaxis, preventing the development of OPC in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy, which causes mucositis as well as neutropenia.10 Posaconazole is effective against Candida species; it also has activity against many filamentous fungi and can reduce the incidence of infections caused by these fungi.11,12 Posaconazole may be the prophylactic drug of choice in certain hospitalized patients-for example, stem cell transplantation recipients who are at risk for disease with invasive filamentous fungi, such as Aspergillus and Mucor species.

Topical agents, such as clotrimazole troches and nystatin, are less effective than orally absorbed agents.10,13

References:

REFERENCES

1.

Odds FC. Candida

and Candidosis. A Review and Bibliography.

London: Bailliere Tindall; 1988:68-92.

2.

Klotz S, Gaur NK, Lake DF, et al. Degenerate peptide recognition by

Candida albicans

adhesins Als5p and Als1p.

Infect Immun.

2004;72:2029-2034.

3.

Rauceo JM, De Armond R, Otoo H, et al. Threonine- rich repeats increase fibronectin binding in the

Candida albicans

adhesin Als5p.

Eukaryot Cell.

2006;5:1664-1673.

4.

Staab JF, Bradway SD, Fidel PL, Sundstrom P. Adhesive and mammalian transglutaminase substrate properties of

Candida albicans

Hwp1. Science. 1999;283:1535-1538.

5.

Sciubba JJ. Denture stomatitis. eMedicine. Fritsch P, Wells MJ, Eisen D, et al, eds. 2007. Available at: http://www.emedicine.com/derm/topics642.htm. Accessed January 30, 2008.

6.

Sohnle PG, Collins-Lech C, Wiessner JH. The zinc-reversible antimicrobial activity of neutrophil lysates and abscess fluid supernatants.

J Infect Dis.

1991;164:137-142.

7.

Ellepola AN, Samaranayake LP. Oral candidal infections and antimycotics.

Crit Rev Oral Biol Med.

2000;11:172-198.

8.

Pappas PG, Rex JH, Sobel JD, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for treatment of candidiasis.

Clin Infect Dis.

2004;38:161-189.

9.

Kraehenbuhl JP, Neutra MR. Molecular and cellular basis of immune protection of mucosal surfaces.

Physiol Rev.

1992;72:853-879.

10.

Clarkson JE, Worthington HV, Eden OB. Interventions for preventing oral candidiasis for patients with cancer receiving treatment.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2007;(1):CD003807.

11.

Klotz SA. Oropharyngeal candidiasis: a new treatment option.

Clin Infect Dis.

2006;42:1187-1188.

12.

Vazquez JA, Skiest DJ, Nieto L, et al. A multicenter randomized trial evaluating posaconazole versus fluconazole for the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in subjects with HIV/AIDS.

Clin Infect Dis.

2006;42:1179-1186.

13.

Gøtzsche PC, Johansen HK. Nystatin prophylaxis and treatment in severely immunodepressed patients.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2002;(4):CD002033.

14.

Budtz-Jörgensen E, Lombardi T. Antifungal therapy in the oral cavity.

Periodontol 2000.

1996;10:89-106.