- Clinical Technology

- Adult Immunization

- Hepatology

- Pediatric Immunization

- Screening

- Psychiatry

- Allergy

- Women's Health

- Cardiology

- Pediatrics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology

- Pain Management

- Gastroenterology

- Infectious Disease

- Obesity Medicine

- Rheumatology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Pulmonology

PTSD May be a Modifiable Risk Factor for Poor T2D Outcomes

Younger US veterans with PTSD and type 2 diabetes who no longer met criteria for PTSD were less likely to initiate insulin and had reduced odds of mortality.

©alstanova@gmail.com/stock.adobe.com

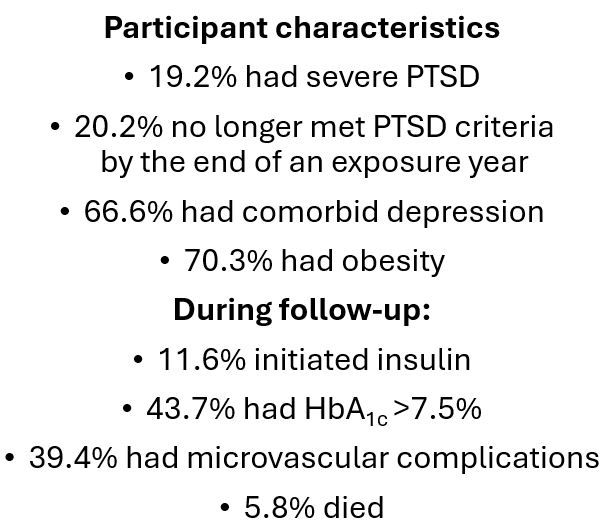

Among a cohort of US veterans, aged 18 to 80 years, with comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and type 2 diabetes (T2D), individuals whose symptoms no longer met diagnostic criteria for PTSD had an 8% lower risk for T2D-related microvascular complications.1 Among veterans aged 18 to 49 years, although not among those aged 50 to 80 years, the shift in PTSD status was associated with a significant 31% reduction in odds of initiating treatment with insulin and significant 61% lower risk of all-cause mortality.1

The findings, from a study published on August 13 in JAMA Network Open, suggest that PTSD may be a modifiable risk factor for poor outcomes in this highly vulnerable population.

“To our knowledge, this is the first evidence that PTSD is a modifiable risk factor, albeit a modest one, for some adverse diabetes outcomes such as microvascular complications,” senior author Jeffrey Scherrer, PhD, professor of family and community medicine and professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at Saint Louis University School of Medicine, said in a university news release.2

The retrospective cohort study tapped deidentified data for 10,002 veterans from US Veterans Health Administration health records from October 1, 2011, to September 30, 2022. Before entropy balancing, used to emulate randomization, ie, to remove differences in distribution of covariates between participants whose PTSD symptoms persisted unchanged and those who no longer met the criteria, participants who no longer met PTSD criteria vs those who still did had similar incidence rates for starting insulin (22.4 vs 24.4 per 1000 person-years [PY]), poor glycemic control (137.1 vs 133.7/1000 PY), any microvascular complication (108.4 vs 104.8/1000 PY), and all-cause mortality (11.2 vs 11.0/1000 PY).1

After Scherrer and colleagues controlled for confounding using weighted data, they reported that no longer meeting criteria for PTSD was associated with a significantly lower risk of microvascular complications (hazard ratio [HR], 0.92; 95% CI, 0.85-0.99).1

Interactions by age group and meeting PTSD criteria and risk of insulin initiation and call-cause mortality were statistically significant in subgroup analyses, according to the study findings. For the younger participants (aged 18 to 49 years) but not those older than that, symptom burden that no longer met criteria for PTSD was linked with a statistically significant lower likelihood of starting insulin (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.53-0.88; P = .003) and a lower risk of death from all causes (HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.19-0.83; P =.008).1

The researchers did not find any significant difference in the association between no longer meeting PTSD criteria and T2D outcomes by sex, race, or by diagnosis of severe PTSD. Among those with depression, however, there was a significant interaction between no longer meeting PTSD criteria and the odds of beginning insulin treatment; the risk was lower among those without depression.1

Study cohort

Among the more than 10 000 veteran participants, more than half (65.3%) were older than age 50 years and the majority (87.2%) were men. More than half self-identified as being White (62.7%), 31.6% as being Black, and 5.7% as being “other” race. Improvement of PTSD was defined for the study as attaining a score of less than 33 on a PTSD checklist, 33 being diagnostic for the condition. All participants were required to have participated in at least 9 PTSD treatment sessions in any 15-week period.

Scherrer and colleagues note that the lower risk of insulin initiation and mortality among younger vs older veterans is “logical,” given the impact of aging on evolution of comorbid conditions that also likely blunts the ability to detect associations in those older than 50 years. The understanding of PTSD as a metabolic disease with underlying mechanisms common to the inflammatory response could in part explain why the condition is a risk factor for prediabetes and T2D, the authors wrote.

Supporting the potential connection between mental illness and poor metabolic health is evidence of an increased risk of T2D among those with PTSD—part of the rationale for the current study to see if amelioration of the latter would impact the former. The authors also cite research that shows individuals with comorbid PTSD and T2D tend to have poor glycemic control, greater likelihood of hospitalization, and poorer self-reported health than those with T2D alone.

The study findings provide “further evidence that we should not separate mental from physical health. Treating the whole patient with comorbid PTSD and diabetes should address both conditions to optimize outcomes,” Scherrer said. Screening for and treating PTSD as part of diabetes care may lead to better clinical outcomes for both conditions." Further, early treatment of the disorder, ie, at younger ages, could decrease the risk of developing insulin-dependent T2D, researchers concluded.

References

Scherrer JF, Salas J, Wang W, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and type 2 diabetes outcome in veterans. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(8):e2427569. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.27569

SLU research: PTSD is a modifiable risk factor for type 2 diabetes, related adverse outcomes. News release. Saint Lous University. August 15, 2024. Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.slu.edu/news/2024/august/ptsd-diabetes-research.php

Phase 3 Data Support Oral Orforglipron for Weight Maintenance After GLP-1–Based Weight Loss

December 19th 2025Topline Phase 3 ATTAIN-MAINTAIN data show oral orforglipron met primary and key secondary endpoints for weight maintenance after prior GLP-1–based injectable therapy in adults with obesity.