- Clinical Technology

- Adult Immunization

- Hepatology

- Pediatric Immunization

- Screening

- Psychiatry

- Allergy

- Women's Health

- Cardiology

- Pediatrics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology

- Pain Management

- Gastroenterology

- Infectious Disease

- Obesity Medicine

- Rheumatology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Pulmonology

Hemoptysis in a Previously Healthy Young Man

A 26-year-old man came to the ED after a week of experiencing fever, chills, dyspnea, aches, and hemoptysis. He had no prior medical history.

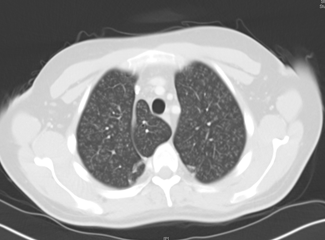

The patient's temperature was 101.5oF (38.6oC). Assessment of lung sounds found decreased air entry associated with bilateral rhonchi in upper and lower lung fields. Chest films showed bilateral perihilar markings suggestive of interstitial pneumonitis (Figure 1). The white blood cell (WBC) count was elevated (24,400/µL). Sputum was collected for culture, which later only showed WBCs, no organisms.

Treatment was initiated with intravenous ceftriaxone and azithromycin. Acetaminophen and ibuprofen were given as needed.

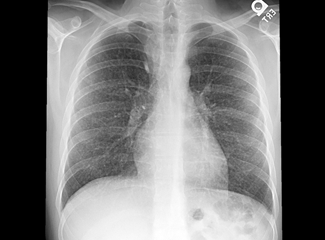

The following day the patient’s temperature was still elevated, ranging from 100oF to 102oF (37.7oC to 38.8oC) and his WBC count was still markedly elevated (between 21,000 and 22,000/µL). His breathing had become more rapid and labored. A CT scan of the chest with contrast (Figure 2) found mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy and a diffuse pattern of miliary nodules throughout both lungs. The findings were highly suggestive of tuberculosis (TB).

Results of a full workup for TB and immunosuppression tests were negative, however. Skin tests for PPD, Candida albicans, and Trichophyton also were negative.

The patient’s respiratory status continued to deteriorate and he required intubation. The original antibiotic regimen was replaced with vancomycin and levofloxacin, and voricanazole and hydrocortisone were added. A bronchoscopy study was performed and bronchial secretions were sent out for cytology, which only showed elevated WBCs, no fungal elements, and negative acid-fast stain.

Based on the clinical picture, imaging, and all the various cultures, what disorders would you include in your differential diagnosis?

The differential included miliary TB, disseminated fungal infections, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

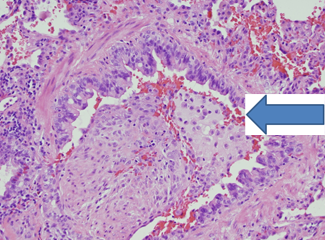

An open lung biopsy was performed 5 days after the patient was intubated. Results showed bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP) (Figure 3).

The final stains for Mycobacteria were negative. The patient’s health improved after a total stay of 38 days and he was discharged. He was to complete a 10-day course of oral erythromycin and at least 3 month course of oral prednisone daily to manage BOOP and reduce inflammation.

Discussion

BOOP was first described in 1985 as an entity distinct from the other lung diseases (eg, interstitial pneumonia and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis).3 BOOP is characterized by granulation tissue in the bronchiolar lumen, alveolar ducts, and some alveoli, and by the infiltration of interstices with mononuclear cells and foamy macrophages.1 It affects persons of all ages; about half of those affected present with a flu-like illness with persistent nonproductive cough, dyspnea, malaise, and weight loss. Hemoptysis, which was seen in this patient, and pleuritic chest pain are very rare findings.

The majority of BOOP cases are idiopathic but many causes have been identified. BOOP is associated with post-pneumonia infection, drug exposure, rheumatologic or connective tissue disease, immunologic disease, and, rarely, environmental exposures.2 Chest radiographs typically show bilateral patchy alveolar infiltrates and nodules. Cavities and effusions are rare as are the miliary nodular pattern, which was seen in this case.4 CT scans can show bilateral areas of consolidation and ground glass opacities in a peripheral location (Table 1).1

Lung biopsy via video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery continues to be the preferred method of diagnosing BOOP. First line therapy is with prednisone for at least 6 months. Erythromycin, inhaled triamcinolone, and cyclophosphamide have also been used.3 BOOP recurs in about a third of patients who receive treatment for less than 1 year. However, BOOP responds to re-treatment with the previously effective dose of prednisone.2

Teaching Points

o When confronted with a patient with respiratory failure, fever, and elevated white count, all efforts to reach the correct diagnosis must be undertaken-- including performing an open lung biopsy.

o Empiric treatment with antibiotics is the standard of care for pulmonary infections; however when a patient is unresponsive, a trial of corticosteroids might be warranted as a diagnostic aid.

o In diagnosing diffuse nodular lesions seen on chest CT, BOOP has become an important consideration as one of the causes.

Pulmonary Nodules

Location

Size

Description

Benign vs. Malignant

Benign when they are juxtaposed to the visceral pleura or an interlobar fissure. Malignant nodules have bias for the better perfused lung bases.

Benign when they are <5 mm in diameter. Metastatic solid organ malignancy when they are ≥1 cm in diameter, round with sharply demarcated borders.

Signs of a benign nodule are granulomata, scars, or intraparenchymal lymph nodes. Cavitation of metastatic lesions occurs in less than 5% of cases and is more likely seen in squamous cell carcinomas.

Abscess

Gravitational distribution with a predilection for the lung bases, the posterior regions of the upper lobes, the axillary regions of the upper lobes, and the superior segments of the lower lobes.

Lesions are between 0.5 and 3 cm in diameter, round, and well-defined.

Patients with bacteremia or recurrent aspiration can get them. Formation of thick-walled cavities is common once the central necrotic debris has gone through a bronchiolar communication.

Septic emboli

Predilection for peripheral areas of the lower lobes.

Multiple 0.5 to 3 cm round or wedge-shaped nodules.

Bacteremia and septic thrombophlebitis may generate septic emboli.

Fungal

Non-specific areas of the lung.

Lesions tend to range from 0.5 to 3 cm in diameter.

Most common fungal infections are in context of histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis, or invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised hosts.

Inflammatory conditions

Various areas throughout the lung.

Multiple round, sharply or poorly demarcated lesions varying in size from 0.5 to 10 cm.

Wegener's granulomatosis, rheumatoid arthritis, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, amyloidosis, and sarcoidosis are examples.

BOOP

Centrilobular.

3 to 5 mm.

Small nodular opacities, basal airspace consolidation, pleural effusions, and bronchial wall thickening can be seen.

Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations

Have bias for the lower lungs and for the middle third of the lung parenchyma.

Lesions are usually well-defined, round, or oval opacities ranging from 1 to 5 cm in diameter.

Abnormal communications between pulmonary veins and arteries and may present as either solitary or, in 30% of cases, multiple pulmonary nodules. When multiple, these malformations are associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia in 50% of cases.

Pneumoconiosis

Usually located in the upper lobes.

Range in size from 1 to 10 cm.

Both coal workers' pneumoconiosis and silicosis may evolve to progressive massive fibrosis or conglomerate masses, yielding a radiographic appearance of multiple pulmonary nodules.

References:

References

1.

Epler GR. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia.

Arch Intern Med.

2001;161:158-164.

2.

Al-Ghanem S, Al-Jahdali H, Hanaa B, Nawaz KA. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia: pathogenesis, clinical features, imaging and therapy review.

Ann Thoracic Med. 2008;3:67-75.

3. Corrin, B. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Chest. 1992;102:7S.

4. Fauci AS, Longo DL, Kasper DL, et al, eds. Approach to the patient with disease of the respiratory system. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc; 2008:1495-1498.

5. Mandel J, Stark P. Differential diagnosis and evaluation of multiple pulmonary nodules. In: Wilson KC, ed: UptoDate. Waltham, MA: 2011.