- Clinical Technology

- Adult Immunization

- Hepatology

- Pediatric Immunization

- Screening

- Psychiatry

- Allergy

- Women's Health

- Cardiology

- Pediatrics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology

- Pain Management

- Gastroenterology

- Infectious Disease

- Obesity Medicine

- Rheumatology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Pulmonology

Emphysematous Pancreatitis in a 61-Year-Old Man

Emphysematous pancreatitis is a rare form of necrotizing pancreatitis. Free air within the pancreatic parenchyma is typically attributed to infection.

A 61-year-old obese man with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension presented to the emergency department with complaints of fatigue and poor oral intake. The patient also complained of a 10-lb weight loss that began approximately 2 weeks before admission but denied any significant abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, steatorrhea, scleral icterus, and jaundice. He had no prior GI history, including a negative history of pancreatitis. He denied alcohol abuse but admitted to prior marijuana use.

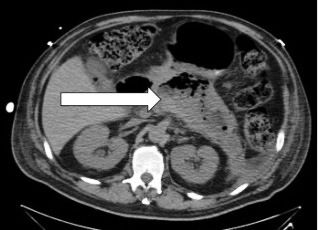

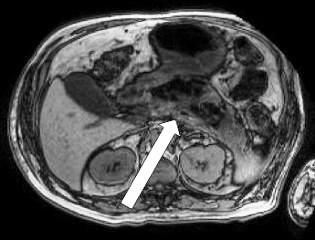

The physical examination was unremarkable except for a blood pressure of 80/60 mm Hg, which corrected with infusion of 2 L of normal saline. Laboratory findings included normal values for a complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, and serum amylase/lipase. CT of the abdomen and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed acute emphysematous pancreatitis with extensive pancreatic necrosis (> 60%), without evidence of gallbladder or biliary tract disease (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1

Figure 2

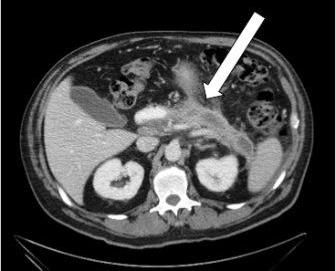

The patient was aggressively managed with IV fluids and IV imipenem and was monitored in the ICU. He remained clinically stable and after 2 days was downgraded to a regular ward, taken off antibiotic therapy, and clinically monitored. A subsequent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed a posterior wall penetrating duodenal ulcer >2 cm in diameter (Figure 3). The patient remained asymptomatic throughout his hospital course, without evidence of clinical or hemodynamic compromise. He was able to tolerate oral intake within 2 days of admission. He was discharged in stable condition with plans to complete high-dose PPI therapy. He has remained stable and emphysematous pancreatitis has resolved (Figure 4).

Figure 3

Discussion

Necrotizing pancreatitis, a severe form of pancreatitis, occurs in up to 20% of patients who have acute pancreatitis.1 At least 30% of the pancreas must show necrosis on CT for a definitive diagnosis. Approximately 30% of patients with necrotizing pancreatitis develop infected necrosis. Mortality rates among these patients ranges from 20% to 40%.2-5 Emphysematous pancreatitis is a rare form of necrotizing pancreatitis. It is characterized by free air within the lesser sac or pancreatic parenchyma, the source of which is typically attributed to infection as opposed to an enteropancreatic fistula.6 Infectious causes are secondary to gas-forming organisms, most commonly polymicrobial infections, including anaerobes and gram-negative bacteria.3-5 Underlying etiologies for enteropancreatic fistulas are numerous. When associated with pancreatitis, however, the most common causes are believed to be complications of pancreatic inflammatory masses secondary to acute pancreatitis or pancreatic pseudocyst drainage.3-5,7

Historically, emphysematous pancreatitis has been managed with broad-spectrum antibiotics and early surgical debridement. Recently, however, case reports/series have shown that patients without evidence of hemodynamic or other systemic compromise have been successfully managed with conservative therapy.2-4

Clinical Features

Clinical presentations of patients with emphysematous pancreatitis can vary widely, from minimally symptomatic to hemodynamic compromise and shock. Typical are findings classically associated with pancreatitis including nausea, vomiting, fever, and epigastric pain. Lab findings will usually reveal a significantly elevated amylase/lipase level and CT scan will show free air within the lesser sac or pancreatic parenchyma. The clinical course of necrotizing pancreatitis is known to be tenuous, frequently complicated by the development of systemic inflammatory response syndrome and multiorgan failure within 1 to 2 weeks of symptom onset.1,2,8 Up to half of the mortality occurs in this time frame,2,9 and so early supportive care is essential. Systemic inflammation will improve; however, in approximately one-third of patients, infected necrosis develops, presumably as a result of gut translocation.2,6

Figure 4

Patients with necrotizing pancreatitis who have emphysematous pancreatitis have a highly variable clinical course. Recent case reports/series describe a less aggressive process with fewer complications and subsequently lower morbidity/mortality compared with the course of general necrotizing pancreatitis.3,5,6 The cause of free air also plays an important role in a patient’s clinical course as well as in the approach to treatment.

Treatment

Treatment for necrotizing pancreatitis traditionally has involved early, aggressive surgical debridement. A more recent study, however, showed that a conservative approach to therapy also is effective.2 Infected necrosis requires broad-spectrum IV antibiotics followed by prolonged oral therapy, with many reports noting meropenem followed by moxifloxacin for up to 2 months. For patients who require surgical intervention, postponement of surgical debridement for up to 1 month is recommended to allow demarcation and organization of the inflammatory mass.2,4,10 The absolute indication for necrosectomy in an infected pancreatic inflammatory mass is still evolving. A recent study found that up to one-third of patients with infected necrosis can be treated with catheter drainage in conjunction with antibiotics.2

For emphysematous pancreatitis, there are no clear management protocols. In patients with hemodynamic and/or systemic compromise, a combination of aggressive management including IV antibiotics, ICU monitoring, and surgical consideration is recommended. Recommendations are less clear, however, in clinically stable cases where the underlying etiology can remain unclear.

In the case presented here, the finding of a penetrating duodenal ulcer provided a possible cause for the presence of air in the pancreas. This finding is similar to that seen in approximately half of patients in a small case series reported in 2009.3 We believe that in clinically stable patients with emphysematous pancreatitis, an EGD should be performed for further evaluation. In those without clinical or laboratory evidence of infection, we recommend limiting the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and instead propose conservative supportive care.

References:

1. Bradley EL III. A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, Ga, September 11 through 13, 1992. Arch Surg. 1993;128:586–590.

2. Van Santvoort HC, Bakker OJ, Bollen TL, et al; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. A conservative and minimally invasive approach to necrotizing pancreatitis improves outcome. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1254-1263.

3. Kvinlaug K, Kriegler S, Moser M. Emphysematous pancreatitis: a less aggressive form of infected pancreatic necrosis? Pancreas. 2009;38:667-671.

4. Adler DG, Chari ST, Dahl TJ, et al. Conservative management of infected necrosis complicating severe acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:98-103.

5. Wig JD, Kochhar R, Bharathy KGS, et al. Emphysematous pancreatitis: radiological curiosity or a cause for concern? JOP. J Pancreas (Online). 2008;9:160-166.

6. Birgisson H, Stefansson T, Andresdóttir A, Möller PH. Emphysematous pancreatitis: a case report. Eur J Surg. 2001;167:918-920.

7. Alexander ES, Clark RA, Federle MP. Pancreatic Ggas: indication of pancreatic fistula. Am J Radiol. 1982;139:1089-1093.

8. Beger HG, Rau B, Mayer J, Pralle U. Natural course of acute pancreatitis. World J Surg. 1997;21:130–135.

9. Johnson CD, Abu-Hilal M. Persistent organ failure during the first week as a marker of fatal outcome in acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2004;53:1340–1344.

10. Uhl W, Warshaw A, Imrie C, et al. IAP guidelines for the surgical management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2002;2:565–573.

11. Ku YM, Kim HK, Cho YS, Chae HS. Medical management of emphysematous pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:453-456.

12. Bazan HA, Kim U. Emphysematous pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:e25.

Phase 3 Data Support Oral Orforglipron for Weight Maintenance After GLP-1–Based Weight Loss

December 19th 2025Topline Phase 3 ATTAIN-MAINTAIN data show oral orforglipron met primary and key secondary endpoints for weight maintenance after prior GLP-1–based injectable therapy in adults with obesity.