- Clinical Technology

- Adult Immunization

- Hepatology

- Pediatric Immunization

- Screening

- Psychiatry

- Allergy

- Women's Health

- Cardiology

- Pediatrics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology

- Pain Management

- Gastroenterology

- Infectious Disease

- Obesity Medicine

- Rheumatology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Pulmonology

Hep C Expert Interview: Gregory T. Everson, MD

Renowned transplant expert Gregory T. Everson, MD, talked with Patient Care about sensitive issues surrounding liver transplant in the era of direct-acting antiviral therapy.

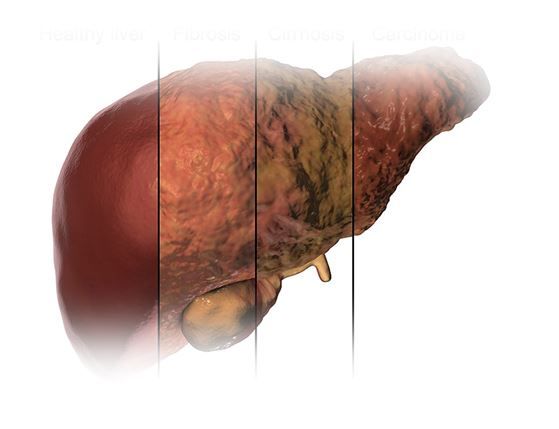

©Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

Transplant issues related to HCV are an active area of research and inquiry, particularly with regard to the use of infected organs. We sat down with transplant expert Gregory T. Everson, MD, to review recent findings and the current state of research. Dr. Everson recently retired from his role as Director of the Section of Hepatology at the University of Colorado. He is now focused on his current passion, liver function tests, as CEO of HepQuant, a company he founded in 2007. Here are some highlights of the interview with Dr. Everson.

Some studies are showing that up to one-third of HCV-infected liver transplant candidates can be removed from the waiting list due to substantial improvement in liver function after treatment with direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy. What are the long-term implications of delisting these individuals?

Dr Everson: Most of these patients who have cirrhosis will experience the long-term benefit of improvement in liver function and experience a slow sustained improvement in liver-related health. Those with significant improvement in liver health are candidates for delisting. However, the big concern is whether they will remain free from risk of liver cancer, since liver cancer is a consequence of cirrhosis.

A recent European study highlighted this potential problem. The study showed that, two years after cure of the HCV and delisting, some of these patients developed liver cancer. This raises the question of whether we should delist these patients at all, because we don't know who's going to get the liver cancer. Perhaps most importantly, if a liver transplant program decides to delist a patient, it behooves the program to continue very careful surveillance for liver cancer--you can't just tell these people, "You're out of the woods and you're going to get better."

"The study showed that, two years after cure of the HCV and delisting, some of these patients developed liver cancer. This raises the question of whether we should delist these patients at all..."

The main study on delisting was a European study, and the US experience may be different. For example, in the European study the mean MELD (model for end-state liver disease) score of delisted patients was 9; typically in the United States, listing for transplant would not occur until MELD score has risen to 15 or higher. Patients with HCV cirrhosis and MELD 9 would be treated with DAAs but would not be listed. Due to this practice, the number of patients listed for liver transplant for HCV cirrhosis has dramatically declined. The current US recommendation after curing HCV in cirrhosis is to maintain surveillance for liver cancer-imaging the liver by ultrasonography or CT or MRI at least annually.

Next: Who can safely receive an HCV-positive liver?

Can HCV-positive donor livers be safely transplanted in HCV-negative individuals? What are the current controversies, and are they getting any closer to resolution?

Dr Everson: Increasingly, transplant centers are considering the use of HCV-positive donor livers for transplantation into HCV-negative recipients. The liver is the organ in the body that harbors HCV and is where HCV replicates. Transplanting an HCV-positive liver transmits HCV infection into a recipient. In the past, this was done rarely, and only as a life-saving measure. The success of DAAs in curing HCV, even in advanced cirrhosis, has kindled interest in broader use of the HCV-positive donor livers; ie, we now have treatment, DAAs, that can cure the HCV infection after the transmission of the infection to a recipient.

"The success of DAAs in curing HCV, even in advanced cirrhosis, has kindled interest in broader use of the HCV-positive donor livers..."

However, this practice remains controversial, primarily for two key reasons. Number one, we don't know whether the outcome for the recipient is the same as the outcomes we've already experienced for other transplant situations. For example, the recipient infected with HCV may have a greater risk of infection and perhaps other transplant-related complications compared to the uninfected recipient. Number two, the payer or other third party must be willing to pay for post-transplant HCV DAA treatment in someone who otherwise would not need HCV DAA treatment.

I would encourage transplant centers embarking on the use of HCV-positive donor livers to carefully consider all the potential outcomes, study the experience, and report the outcomes. Multicenter studies are ongoing.

Next: Should waitlist patients be treated with DAAs before or after transplant?

Should waitlist patients be treated with DAAs before or after transplant?

Dr Everson: One specialized issue needs discussion, which is whether the HCV patient on the waiting list should be treated before or after liver transplantation. The advantages of treating before transplant are that the patient may improve, delist, and not need transplant. But as noted above, not all improve and there is still a risk for liver cancer. Another strategy, especially for the more advanced cases with severe liver disease, is to wait until after the liver transplant to treat the patient. This strategy also gives the recipient who has ongoing HCV infection the option to receive an HCV-positive donor liver. The outcome for an HCV-positive recipient who receives an HCV-positive donor liver is similar to an HCV-positive recipient who receives an HCV-negative donor liver.

In the kidney transplant setting, one recent cost-effectiveness analysis showed that the preferred approach is to transplant an HCV-infected kidney followed by DAA treatment, as opposed to DAA treatment followed by transplant of an uninfected kidney. What are the clinical considerations with regard to kidney transplant in HCV infected individuals?

Dr Everson: There are certain strategies that are becoming increasingly accepted. One of them is using HCV-positive organs for transplantation into HCV-positive recipients. That’s true whether it's a kidney, liver, heart, or lung transplant; typically there is no immediate need to treat that recipient with DAAs if they have otherwise stable liver disease. If they remain HCV-positive on the waiting list they can access a HCV-positive donor organ. The recent cost effectiveness analysis found substantial benefit to this approach since earlier access to transplant due to acceptance of an HCV-positive donor kidney shortens time on dialysis and the costs, morbidity, and mortality of dialysis.

"The recent cost effectiveness analysis found substantial benefit to this approach since earlier access to transplant due to acceptance of an HCV-positive donor kidney shortens time on dialysis and the costs, morbidity, and mortality of dialysis."

Next: Transplant hearts from HCV-infected donors - will this work?

There is also interest in transplanting hearts from HCV-infected donors into non-infected recipients, partly on grounds that the risk of dying from a HCV-positive donor is orders of magnitude lower than not getting a transplant. Do you agree that this is a promising strategy?

Dr Everson: I would agree fully with that approach. If you have an excellent functioning donor heart from a HCV-positive donor, it definitely should be considered for transplantation into a heart recipient. Heart transplant recipients are often in desperate circumstances and the transplant is essentially life-saving. As previously stated, the chance for cure with current DAAs is over 95% and approaches 100%. An uninfected heart recipient presumably has a normal liver which likely could tolerate an acute infection with HCV. Even if the recipient were to experience significant hepatic injury, institution of DAA treatment early in the post-transplant course could abort further liver deterioration by eradication of the HCV infection.

"Even if the recipient were to experience significant hepatic injury, institution of DAA treatment early in the post-transplant course could abort further liver deterioration by eradication of the HCV infection."

Nonetheless, DAA is not 100% guaranteed to be effective and patients and providers need to be ready to accept the low but potential risk that the DAA treatment will be ineffective and that the recipient could experience progressive hepatic disease post-transplant. Despite these caveats, in the vast majority of cases post-transplant HCV will be eradicated by DAA treatment and the recipient of an organ from an HCV-positive donor will likely live out his post-transplant life free from HCV.

No Rx Required for COVID-19 Vaccination But ACIP Calls for Better Informed Consent Process

September 22nd 2025The ACIP on September 19 narrowly voted against requiring a prescription to get the shot but urged more detailed discussion of vaccine risks during shared decision making conversations.