- Clinical Technology

- Adult Immunization

- Hepatology

- Pediatric Immunization

- Screening

- Psychiatry

- Allergy

- Women's Health

- Cardiology

- Pediatrics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology

- Pain Management

- Gastroenterology

- Infectious Disease

- Obesity Medicine

- Rheumatology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Pulmonology

West Nile Virus-The Rodney Dangerfield of Infections

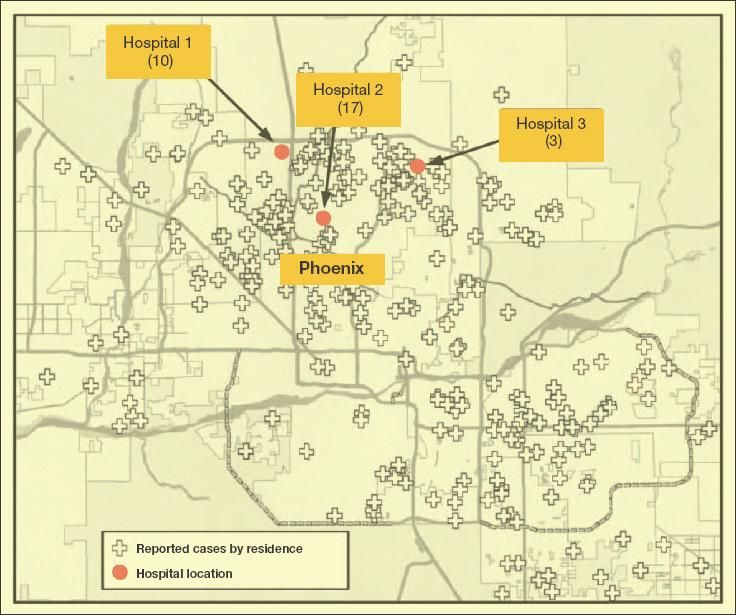

WNV first appeared in the United States in 1999.1 This infection "got no respect" even though it caused significant morbidity and mortality while crossing the United States unabated for the past 9 years. Patients died mainly of neuroinvasive complications such as encephalitis and a polio-like paralysis. The lack of respect became a reality to clinicians in Phoenix in 2004 when they found themselves poorly prepared to manage the many acutely ill patients affected by WNV. That there was a lack of practical information about how to manage WNV became readily apparent to these clinicians.

FigureRodney Dangerfield lamented that he "got no respect" but was a good comedian. This thought is analogous to West Nile virus (WNV). This mosquito- borne virus has proved itself to be a capable pathogen, causing an epidemic in the United States despite the US health care system being theoretically prepared to prevent a bioterrorism attack. I would like to make the case that the WNV epidemic was the result of bioterrorism. The epidemic illustrated how poorly prepared we are to meet the challenges posed by this and other agents that may not get the respect they deserve.

WNV first appeared in the United States in 1999.1 This infection "got no respect" even though it caused significant morbidity and mortality while crossing the United States unabated for the past 9 years. Patients died mainly of neuroinvasive complications such as encephalitis and a polio-like paralysis. The lack of respect became a reality to clinicians in Phoenix in 2004 when they found themselves poorly prepared to manage the many acutely ill patients affected by WNV. That there was a lack of practical information about how to manage WNV became readily apparent to these clinicians.

Challenges included (1) inability to adequately prepare for the uniqueness of the disease or seriousness of the illness, (2) inability to diagnose the infection in a timely way, (3) lack of adequate information on how to treat the infection, and (4) lack of information about coordination regarding prevention measures. These and other problems support the idea that there was a lack of preparedness at the grassroots level. It is not that nothing was done but that the threat of WNV was not given due respect politically and in the scientific community compared with avian influenza virus and Bacillus anthracis, 2 agents that so far have caused comparatively minimal damage in the United States.

I am in a reasonable position to raise issues about how the WNV epidemic has been handled in the United States. I have both research and clinical experience in arboviruses, having worked in arbovirology in my early career with the NIH, and being in private practice for more than 25 years. Most of the early information on WNV infections came from clinicians turned arbovirologists1 and arbovirologists turned clinicians.2

Arboviruses have not been a serious problem in the United States, and this may partly be why WNV has not received the attention it should. Bioterrorism, however, has received a lot of attention. Was the WNV epidemic the result of bioterrorism? Using relatively simple techniques in a low-tech laboratory, enormous numbers of mosquitoes can be infected with WNV.3 Of interest is that the strain of WNV that caused the epidemic in the United States originated in the Middle East.4

To get an idea of some of the problems clinicians faced in caring for critically ill patients, picture diagnostic laboratory tests taking 6 or more days before the results become known, as detailed in our article in this issue of Infections in Medicine. An aggravating problem was the knowledge that diagnostic tests for WNV infection were available but not readily accessible and did not allow for rapid turnaround time at the community hospital level. The years between 1999 and 2004 should have been enough time to establish rapid diagnostic tests and an algorithm on how best to deal with critically ill patients with WNV.

Most clinicians might know that WNV is an RNA virus and thus is resistant to acyclovir. However, they may be unaware that WNV, like hepatitis C virus (HCV), belongs to the genus Flavivirus. Most clinicians know that interferon and ribavirin have been used successfully in the treatment of HCV infection. Thus, it seemed reasonable to use these drugs for the critically ill patient with WNV infection. We postulated that these would be better alternatives than ceftriaxone or acyclovir. Faced with critically ill patients on a ventilator who were unable to move against gravity, therapy with interferon and ribavirin seemed a more reasonable approach than "supportive" care.2 If desperate clinicians could come to this conclusion in less than 5 years after the initial WNV outbreak, why was more information about this therapeutic option not available?

I give the response of the NIH and CDC in assigning the WNV epidemic a failing grade. The slow response has allowed WNV to go from epidemic to endemic status. Now we will be faced with WNV infections every year wherever there are mosquitoes in the United States. My analysis is that more resources were being put into the study of other infectious threats, such as smallpox and avian influenza, than into the study of WNV infection, for politically rather than medically expedient reasons. Unfortunately, the NIH and CDC may lose objectivity when nonmedical governmental purse strings are influencing their decisions.

The United States has enough resources, experience, and knowledge to identify and deal with infectious disease problems uninfluenced by politics, media, and government funding pressures. A retrospective look at the WNV epidemic offers the chance to reexamine and improve efforts on how to deal with such epidemics.

Food for thought: $100,000 should be awarded to any physician who first recognizes a bioterrorism agent. The astute physician who recognized the first case of anthrax deserved such an award. Also, an independent advocacy group, such as the Infectious Diseases Society of America, should be engaged to generate the expertise needed and a more rapid response to suspected infectious bioterrorist threats.

References:

- Nash D, Mostashari F, Fine A, et al; 1999 West Nile Outbreak Response Working Group. The outbreak of West Nile virus infection in the New York City area in 1999. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1807-1814.

- Petersen LR, Marfin AA. West Nile virus: a primer for the clinician. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:173-179.

- Rosen L, Gubler D. The use of mosquitoes to detect and propagate dengue viruses. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1974;23:1153-1160.

- Klee AL, Maidin B, Edwin B, et al. Long-term prognosis for clinical West Nile virus iInfection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1405-1411.