- Clinical Technology

- Adult Immunization

- Hepatology

- Pediatric Immunization

- Screening

- Psychiatry

- Allergy

- Women's Health

- Cardiology

- Pediatrics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology

- Pain Management

- Gastroenterology

- Infectious Disease

- Obesity Medicine

- Rheumatology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Pulmonology

Trachealization of the Esophagus

Eosinophilic esophagitis is often misdiagnosed as gastroesophageal reflux disease but does not respond to acid suppression therapy. Here, a close-to-textbook case.

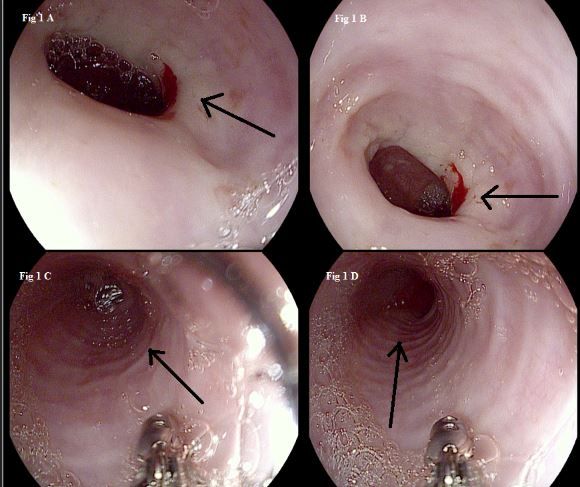

Figure 1.

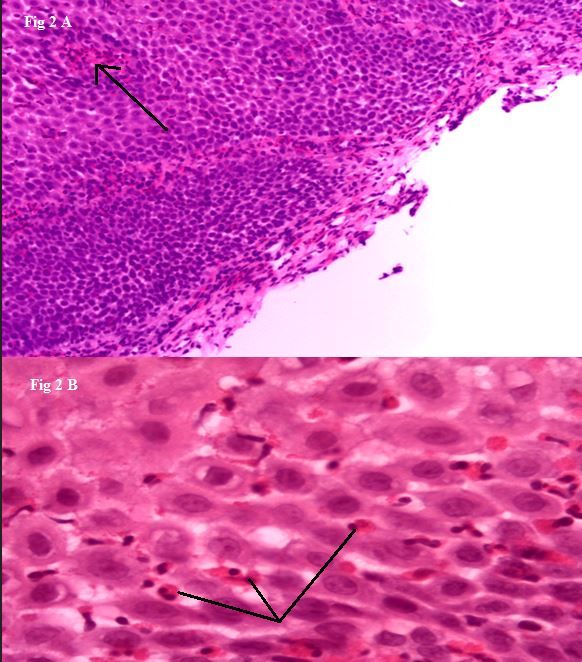

Figure 2.

A 44-year-old woman presented with complaints of progressive dysphagia for solids of 2 weeks’ duration. She described it as a feeling of food getting stuck a few seconds after swallowing. It was not associated with cough or nasal regurgitation. The patient had associated nausea and vomiting but no fever or weight loss. She denied heartburn, regurgitation of food particles, pain during swallowing, chest discomfort, and hematemesis.

The patient had a history of moderate persistent asthma that was somewhat well controlled with inhaled corticosteroids and a long-acting beta-agonist. She also had a history of stage 2 colon cancer that was managed with left hemicolectomy and 12 cycles of chemotherapy 2 years earlier. She was an ex-smoker and denied any alcohol or illicit drug abuse. The patient’s physical examination findings and laboratory data were unremarkable.

Diagnosis

Endoscopy showed thickened white asymmetrical mucosa at the level of the gastroesophageal junction (Figure 1 A and B, black arrows) and felinization, or trachealization, of the esophagus throughout (Figure 1 C and D, black arrows). Tissue biopsy of the gastroesophageal junction revealed abundant eosinophils in the esophageal epithelium, lamina propria, and a minute fragment of the underlying gastric mucosa (Figure 2 A and B, black arrows). These findings were suggestive of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE).

The patient was started on a regimen of omeprazole 40 mg daily and was advised to follow the 6-food elimination diet, which removes the 6 most common foods that have been seen in allergic diseases: milk, egg, soy, wheat, peanuts, and fish/shellfish. She was instructed to use a dry swallowing technique when taking her inhaled fluticasone as part of treatment for the EoE. She was also told to not eat or drink for 30 minutes after taking the medication so that it would coat the esophagus for an optimal period. She was also instructed to swish and spit or to brush her teeth after each use of swallowed corticosteroid to avoid adverse effects such as oral thrush. If swallowing the fluticasone proved difficult, another option would be to combine budesonide with other components (eg, a sweetener) to form a slurry that can be easily swallowed. She was asked to follow up in 1 month for symptom reassessment and to plan for a repeated endoscopy to assess treatment response. At the time of this writing, she has not yet returned for follow-up.

Discussion

EoE has been defined by a panel of experts as “a chronic, immune/antigen-mediated esophageal disease characterized clinically by symptoms related to esophageal dysfunction and histologically by eosinophil-predominant inflammation that is not responsive to acid blockade with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), unlike gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or PPI responsive esophageal eosinophilia.”1

Landres and associates2 first described EoE in 1978. Ever since, the disease has been recognized increasingly as one of the major causes of dysphagia, food impaction, and food regurgitation, especially in the younger population. Among patients who have undergone an outpatient upper endoscopy, the prevalence varies between 5% and 16%; it is highest among patients who present with dysphagia.3

The diagnosis is made when more than 15 eosinophils per high-power field are seen in the esophageal epithelium. The pathophysiology has been linked to allergic and genetic causes.4

Typical findings on an esophagoduodenoscopy that imply the presence of EoE include attenuation of subepithelial vascular pattern, linear furrowing that may extend along the whole length of the esophagus, and surface exudates composed of eosinophils or abscesses or strictures.5,6

One of the most characteristic and frequently quoted patterns is that of stacked circular rings, or felinization, so called because they are present in the cat esophagus. This has been postulated to be the result of lamina propria and dermal papillary fibrosis caused by the mediators that stimulate eosinophils or through the effect of eosinophils themselves.7

Treatment

Treatment of patients with EoE centers around the 3 Ds: diet, drug therapy, and dilatation.

• Dietary treatment. Approaches include skin prick testing and atopy patch testing for food allergies and subsequent elimination of foods that have positive test results, as well as cow’s milk because of its poor negative predictive value on testing. The other option is the 6-food elimination diet, which advocates removing the foods that account for the majority of IgE-mediated food reactions (milk, egg, soy, wheat, peanuts/tree nuts, and fish/shellfish).8

• Drug therapy. The mainstay is the use of topical corticosteroids (fluticasone, budesonide) that can lead to a rapid improvement of active EoE, both clinically and histologically.

• Dilatation. Esophageal dilatation of EoE-induced strictures is effective, but it has no effect on the underlying inflammation.

The long-term prognosis for patients with EoE remains unclear. Symptoms usually recur in those who are treated with a short course of corticosteroids.9 Thus, maintenance therapy with topical corticosteroids or dietary restriction or both should be considered for all patients, particularly those who have severe dysphagia or food impaction, high-grade esophageal stricture, and rapid symptomatic/histologic relapse after initial therapy.

References:

1. Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3-20.

2. Landres RT, Kuster GG, Strum WB. Eosinophilic esophagitis in a patient with vigorous achalasia. Gastroenterology. 1978;74:1298-1301.

3. Veerappan GR, Perry JL, Duncan TJ, et al. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in an adult population undergoing upper endoscopy: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:420-426.

4. Blanchard C, Wang N, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis: pathogenesis, genetics, and therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;7:1054-1059.

5. Straumann A, Spichtin HP, Bucher KA, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: red on microscopy, white on endoscopy. Digestion. 2004;70:109-116.

6. Müller S, Pühl S, Vieth M, Stolte M. Analysis of symptoms and endoscopic findings in 117 patients with histological diagnoses of eosinophilic esophagitis. Endoscopy. 2007;39:339-344.

7. Fox VL. Eosinophilic esophagitis: endoscopic findings. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2008;18:45-57; viii.

8. Lucendo AJ, Arias Ã, González-Cervera J, et al. Empiric 6-food elimination diet induced and maintained prolonged remission in patients with adult eosinophilic esophagitis: a prospective study on the food cause of the disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:797-804.

9. Helou EF, Simonson J, Arora AS. 3-yr-follow-up of topical corticosteroid treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis in adults [erratum in: Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2308]. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2194-2199.

Clinical Tips for Using Antibiotics and Corticosteroids in IBD

January 5th 2013The goals of therapy for patients with inflammatory bowel disorder include inducing and maintaining a steroid-free remission, preventing and treating the complications of the disease, minimizing treatment toxicity, achieving mucosal healing, and enhancing quality of life.