Primary Care Primer for Headache Management, with Morris Levin, MD

ACP 2025. The director of the UCSF Headache Center built an evidence-based framework for diagnosing and treating headache disorders seen in primary care.

Headache disorders are one of the most common nervous system disorders, affecting nearly half the general population. At the American College of Physicians Internal Medicine Meeting 2025, Morris Levin, MD, professor of neurology at the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences and director of the UCSF Headache Center, in San Francisco, provided evidence-based guidance on headache management for internists, addressing acute headache approaches, neuroimaging indications, and migraine treatment options.

Diagnostic Framework for Headache

To start, Levin outlined a framework distinguishing between acute/new headaches and chronic/recurring patterns. For acute headaches, the focus should be on detailed neurological assessment, while chronic headache evaluation requires documentation of frequency, triggers, and accompanying symptoms.

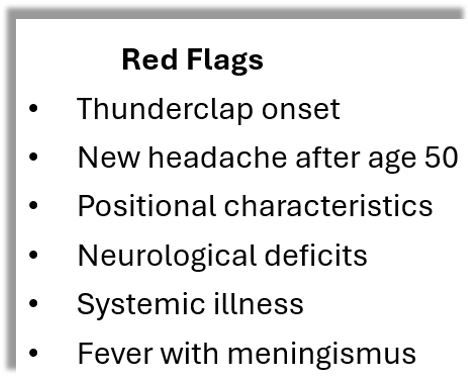

Most chronic recurring headaches are migraine, Levin said, but vigilance for secondary causes is essential, especially in the presence of "red flags," (below). Levin cautioned, clinicians should be vigilant for secondary causes. For thunderclap headaches specifically, ie, severe and sudden in onset, reaching peak intensity within seconds, he described a systematic approach to assessment, beginning with noncontrast CT imaging. If findings are negative, move on to lumbar puncture for xanthochromia. If results are nondiagnostic, Levin said vascular imaging is indicated (CTA, MRA, MRV), to evaluate for aneurysm, RCVS, vasculitis, PRES, or venous thrombosis.

He stressed that a diagnosis of migraine and treatment for the disorder should only be pursued once all potential secondary causes have been excluded.

Acute Migraine Management

For outpatient management, Levin reviewed a tiered approach, highlighting both established and newer migraine-specific therapies:

- Triptans, including newer formulations: sumatriptan nasal powder (Onzetra) and zolmitriptan microarray patch (Qtrypta)

- CGRP receptor antagonists: ubrogepant (Ubrelvy), rimegepant (Nurtec), and zavegepant (Zavzpret)

- Lasmiditan (Reyvow) for individuals with cardiovascular contraindications to triptans

- Non-pharmacologic interventions including neuromodulation devices

Preventive Therapies

Current guidelines recommend nonspecific migraine treatments as first-line prophylactic medications:

- Topiramate (100-200 mg at bedtime)

- Propranolol (80 mg twice daily)

- Nortriptyline (25-75 mg at bedtime)

- Candesartan (4-16 mg daily)

Levin offered practical guidance on the 4 FDA-approved anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies (erenumab, fremanezumab, galcanezumab, and eptinezumab), noting their different administration routes and target mechanisms. The CGRP inhibitor class often produce effects within the first month of treatment, Levin noted, with "impressive" response rates compared to traditional preventives.

While acknowledging their efficacy, Levin advised judicious use of CGRP antagonists in patients with cardiovascular risk factors, gastrointestinal disorders, or inflammatory conditions due to the widespread distribution of CGRP receptors throughout body tissues.¹

For individuals with inadequate response, Levin presented evidence supporting combination approaches, particularly the synergistic effects observed when CGRP antagonists are combined with onabotulinumtoxinA injections,²⁻⁴ which work through complementary mechanisms affecting CGRP pathways, he noted.

Headache Management During Pregnancy

While approximately 80% of women with pre-existing migraine experience improvement by the second trimester, new or worsening headaches during pregnancy warrant careful evaluation for migraine, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, cerebral venous thrombosis during the first and second trimester, and preeclampsia/eclampsia, intracranial hemorrhage, RCVS, PRES, in late pregnancy and during the postpartum period.

For acute treatment, Dr. Levin advocated beginning with non-pharmacologic interventions. When medications are necessary:

- Acetaminophen should be used cautiously, particularly in the third trimester⁵⁻⁶

- NSAIDs are contraindicated in the first and third trimesters

- Triptans have robust safety data from large cohort studies

For preventive therapy during pregnancy, recommendations included:

- Memantine and cyproheptadine (Category B)

- Beta-blockers (tapered before delivery)

- Riboflavin 400 mg daily and coenzyme Q10 300 mg daily

Levin advised against using CGRP-targeted therapies during pregnancy, recommending discontinuation 4-6 months before conception.

Cluster Headache Management

For cluster headache, Levin outlined a dual approach focusec on breaking the cycle (typically with short-course prednisone) and implementing effective prophylaxis with verapamil, valproate, or the CGRP monoclonal antibody galcanezumab. For acute attacks, he emphasized the importance of high-flow oxygen therapy and discussed the emerging evidence for psilocybin as a potential treatment option based on preliminary studies showing promising results for both acute relief and cycle prevention.

Levin also discussed emerging evidence for psilocybin as a potential treatment option for both acute relief and cycle prevention.⁸⁻⁹

On balance, Levin's approach to the topic integrated pathophysiologic mechanisms with clinical trial data and practical management strategies, creating a comprehensive, evidence-based framework for diagnosing and treating the spectrum of headache disorders encountered in clinical practice.

References

1. Maassen Van Den Brink A, Meijer J, Villalón CM, Ferrari MD. Wiping out CGRP: potential cardiovascular risks. *Trends Pharmacol Sci*. 2016;37(9):779-788.

2. Berman G, Croop R, Kudrow D, et al. Safety of rimegepant, an oral CGRP receptor antagonist, plus CGRP monoclonal antibodies for migraine. *Headache*. 2020;60(8):1734-1742.

3. Silvestro M, Tessitore A, Scotto di Clemente F, et al. Erenumab efficacy on comorbid migraine and fibromyalgia: a case series. *J Headache Pain*. 2021;22(1):124.

4. Scuteri D, Adornetto A, Rombolà L, et al. New trends in migraine pharmacology: targeting calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) with monoclonal antibodies. *Front Pharmacol*. 2022;10:363.

5. Brandlistuin I, Ystrom E, Nulman I, et al. Prenatal paracetamol exposure and child neurodevelopment: a sibling-controlled cohort study. *Int J Epidemiol*. 2013;42(6):1702-1713.

6. Liew Z, Ritz B, Rebordosa C, et al. Acetaminophen use during pregnancy, behavioral problems, and hyperkinetic disorders. *JAMA Pediatr*. 2014;168(4):313-320.

7. Goadsby PJ, Dodick DW, Leone M, et al. Trial of galcanezumab in prevention of episodic cluster headache. *N Engl J Med*. 2019;381(2):132-141.

8. Sewell RA, Halpern JH, Pope HG Jr. Response of cluster headache to psilocybin and LSD. *Neurology*. 2006;66(12):1920-1922.

9. Schindler EA, Gottschalk CH, Weil MJ, et al. Indoleamine hallucinogens in cluster headache: results of the Clusterbusters medication use survey. *J Psychoactive Drugs*. 2022;47(5):372-381.