- Clinical Technology

- Adult Immunization

- Hepatology

- Pediatric Immunization

- Screening

- Psychiatry

- Allergy

- Women's Health

- Cardiology

- Pediatrics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology

- Pain Management

- Gastroenterology

- Infectious Disease

- Obesity Medicine

- Rheumatology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Pulmonology

Obesity:

Over the past 20 years, obesity has reached epidemic proportions in the United States and throughout the world. The need for effective prevention and treatment is thus more urgent than ever.

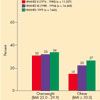

Over the past 20 years, obesity has reached epidemic proportions in the United States (Figure 1) and throughout the world.1,2 The need for effective prevention and treatment is thus more urgent than ever.

Obesity results from an imbalance between energy ingested and energy expended. To be effective, treatment must affect one or both sides of this energy equation. In this article, I discuss 5 different approaches to the problem of obesity-behavior therapy, diet, exercise, medications, and surgery-and assess their efficacy.

MECHANISMS OF WEIGHT GAIN AND LOSS

The most effective therapy for obesity would reduce a patient's weight to normal levels and keep it there. At present, no treatment can produce such results. Figure 2 shows several typical patterns of weight loss and weight loss maintenance, as well as the usual pattern of slow, steady weight gain.

All treatments produce some degree of weight loss followed by a plateau, which results from the body's resistance to the continuing loss of tissue. This plateau concerns patients-and often health professionals-because it occurs at a higher weight than their goal. However, such a plateau also occurs with treatment of hypertension and hyperlipidemia.

Figure 2 also shows that patients tend to regain weight they have lost. Regaining weight can occur slowly-at the rate of gain seen in the general population-or it can occur more rapidly, after effective therapy is discontinued. Again, this phenomenon is similar to that seen in the treatment of hypertension: when an effective antihypertensive is discontinued, the patient's blood pressure can be expected to slowly rise and eventually reach baseline or even higher levels.

BEHAVIOR THERAPY

A behavioral approach to weight loss was first introduced in 1967.3 Over the past 30 years, the original techniques have been steadily improved on. All behavioral programs are designed to:

- Identify and change the antecedents to eating.

- Characterize and improve a person's eating style.

- Reward improved eating behavior.

Retrospective analysis has shown that several strategies are particularly useful.4 These include self-monitoring of eating habits, a lower-fat diet, increased physical activity, and a support system to reward successful behavior. Structured meal plans (or written menus or portion-controlled foods) are also useful.5 By providing broad access to behavioral techniques, the Internet is proving to be a valuable tool for those interested in this approach to weight loss.

Controlled trials showed that weight losses average nearly 10% in behavioral programs that last more than 16 weeks.5 In programs that last up to 24 weeks, weight loss is as much as 10% of initial body weight and the retention is more than 75%.5

The major problem with behavioral strategies is that patients tend to regain weight after leaving a structured program. Behavior therapy can produce long-term weight loss-provided the program is continued.Recent research has focused on how to extend the impact of behavioral programsover longer periods.

Behavior therapy is particularly effective in overweight adolescents. Solid 10-year data show that such therapy can reduce the degree of overweight that lasts into adulthood.6

Self-help groups and commercial weight loss programs have offered help to many persons, but objective data on their efficacy are limited. Weight Watchers has been one of the longest-lasting groups, and a recent study suggests that persons who follow their program experience greater weight loss than those in a control group.7 Other groups, such as Take Off Pounds Sensibly (TOPS) and Overeaters Anonymous (OA), are able to provide support and guidance for some persons.

DIET

The essential element of any diet is reduction of the total caloric intake. Many diets have been recommended over the 150 years since William Banting published his famous "Letter on Corpulence" in 1863. One of the most popular has been the low-carbohydrate diet.8 The fact that new diets continue to appear suggests that none of them has a magic formula; if one did, none of the others would have succeeded in the marketplace.

Fat. Several reviews show that low-fat diets are associated with weight loss.9 A number of factors affect the effectiveness of a low-fat diet, including:

- Initial weight. Overweight persons lose more on a low-fat diet than those of normal weight.

- Amount of fat removed from the diet. The greater the reduction in fat intake, the more weight is lost.

- Palatability of the diet. A very low-fat diet can be difficult for many persons to adhere to. The best advice is to reduce consumption of saturated fats and trans-fatty acids and to lower total fat intake to as near to 25% of total caloric intake as possible.

A recent study showed that replacing fat with olestra, a nondigestible fat substitute, reduced body weight by 6% and body fat by nearly 20% over 9 months, whereas a standard reduced-fat diet with the same amount of available fat (25% of the total caloric intake) was relatively ineffective.10Currently, olestra is available only as an ingredient in certain low-fat snack foods. Its use can reduce the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins.

Carbohydrates and fiber. Intake of both digestible carbohydrates and indigestible carbohydrates (fiber) can affect total food consumption.11 Although recent studies show that substituting starch for sugar does not produce greater weight loss,12 the digestibility of the starch consumed may have an effect. Diets with a low glycemic index (ie, those that contain foods with less-digestible starch that result in a lower rise in glucose levels) produce greater satiety than diets with a high glycemic index.13 The glycemic load (glycemic index × carbohydrate intake) may also be important. In the Nurses Health Study, the glycemic load was related to the risk of heart disease and diabetes.14

Calcium. Nearly 20 years ago, data collected by the National Center for Health Statistics demonstrated a negative relationship between body mass index (BMI) and calcium intake. More recently, a strong inverse relationship was found between calcium intake and the risk of being in the highest quartile of BMI.15

These findings prompted evaluation of the effects of calcium supplementation on weight loss. In prospective trials, subjects who received oral calcium lost more weight than those who received placebos. Increasing calcium from 0 to nearly 2000 g/d was associated with a reduction in BMI of about 5 units.16 These data suggest that low calcium intake has played a role in the current epidemic of obesity. Calcium supplementation may be of value for overweight women whose daily intake of the mineral is less than the recommended amount.

EXERCISE

Increased physical activity can reduce cardiovascular risk.17 In addition, the Diabetes Prevention Program has shown that a program of diet and exercise can reduce by 58% the number of persons who progress from impaired glucose tolerance to frank diabetes.18 However, for many overweight persons, who already expend more energy on everyday activities than persons of normal weight, exercise can be a challenge. For these patients, walking is often the best exercise.

Persons who perform a substantial amount of supervised exercise can achieve significant weight loss. However, for many patients, exercise increases weight loss only slightly, most likely because they fail to maintain the prescribed level of physical activity.

Exercise is most helpful in the maintenance of a lower body weight. A survey of persons who successfully maintained weight loss showed that their level of regular exercise was significantly higher than that of persons who had never been overweight.19 Some reports-but not all-suggest that another benefit of exercise is that it may prompt the body to conserve protein while a person is dieting.

MEDICATIONS

For which patients? Give serious consideration to medical therapy for patients with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 and those with a BMI greater than 27 kg/m2 who have diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance, hypertension, or heart disease (Algorithm). Two strategies can be used to treat overweight patients:

- For those with comorbidities, individual drugs can be used to treat each comorbidity (ie, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and sleep apnea can all be treated separately).

- Patients with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 can be treated with antiobesity drugs; these can be used as an alternative to-or in addition to-drugs for comorbid conditions.

Current antiobesity drugs include appetite suppressants that act on the CNS and orlistat, which blocks pancreatic lipase (Table). Also, a number of new agents are being studied (Box).

Agents for short-term use. Most of these drugs were reviewed and released for marketing more than 20 years ago; they are approved for short-term use only.20 There are 2 reasons why approval was granted only for short-term use. First, almost all studies of these agents have been short-term. Second, the FDA and the Drug Enforcement Administration are concerned about the potential for abuse and thus have restricted the prescription of these drugs to "only a few weeks"-which is usually interpreted as up to 12 weeks.

The withdrawal of fenfluramine and dexfenfluramine from the market in 1997 after valvular heart disease developed in patients who took these drugs has further compounded the concern of health authorities, physicians, and the public about the safety of appetite suppressants. Because of the regulatory limitations and the lack of longer-term data on safety and efficacy, the use of drugs approved only for short-term treatment must be carefully justified. They may be effective in initiating treatment and in helping a patient who is relapsing, but they can be used only for a few weeks.

Agents for long-term use.Sibutramine is approved in the United States for long-term use. This drug can produce weight loss of 10% or more.21,22 Side effects include dry mouth, asthenia, insomnia, and constipation. Sibutramine also produces a small increase in heart rate (between 2 and 5 beats per minute) and a small rise in blood pressure (between 2 and 4 mm Hg). Clinical data show no evidence of valvulopathy associated with its use.23Blood pressure must be carefully monitored in all patients who take this drug, and it is contraindicated in patients with stroke, congestive heart failure, or recent myocardial infarction. Sibutramine should not be used with other serotonergic agents or drugs that inhibit monoamine oxidase.

Orlistat, an agent that blocks intestinal lipase, has been approved for long-term use in the United States. In clinical trials that lasted up to 2 years, orlistat was associated with a mean weight loss of up to 10% at the end of 1 year in patients whose prescribed diet included 30% fat.24-27 Because the drug blocks pancreatic lipase in the intestine, fecal fat loss is increased. Major side effects related to the release of undigested triglycerides (including transient diarrhea, anal leakage, and urgency) were seen in some patients. These usually occurred within the first month and were reported with reduced frequency over time; from this it can be inferred that patients learned to use the drug effectively in relation to dietary intake of fat. The effective use of this medication involves good dietary counseling.

The combination of ephedrine and caffeine has been studied in a randomized 6-month clinical trial in overweight patients.28 After 6 months, patients treated with ephedrine and caffeine had lost more weight than those who received placebo and than those treated with ephedrine alone or caffeine alone. This research has been used to market herbal preparations that contain ephedra alkaloids with or without caffeine. A clinical trial has shown that an herbal ephedra/caffeine preparation results in significantly greater weight loss than placebo.29 All participants were followed with Holter monitoring and ambulatory blood pressure measurements. The only significant difference between those who received the ephedra/caffeine preparation and those who received placebo was a small rise in heart rate in the ephedra/caffeine–treated group.

SURGERY

More than 40 years ago, various bypass operations were introduced that reduced the absorptive surface available to GI contents. At present, the principal surgical procedures used to treat obesity are:

- The gastric bypass.

- The vertical banded gastroplasty.

- The gastric band (which allows a constrictive band around the stomach to be expanded by the injection of saline into a subcutaneous reservoir).

During the 1990s, the introduction of laparoscopic surgery and advances in laparoscopic techniques increased the safety of these procedures. Although surgery was originally recommended only for persons with a BMI greater than 40 kg/m2, studies have shown such marked benefits that it has been suggested that the threshold BMI be reduced to 35 kg/m2-or even lower if significant risk factors are present.30

References:

REFERENCES:

1.

NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative Expert

Panel on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatmentof Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Clinicalguidelines on the identification, evaluation, andtreatment of overweight and obesity in adults-theevidence report. Obes Res. 1998;6(suppl 2):51S-209S.

2.

World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventingand Managing the Global Epidemic. Report of a WHOConsultation. Geneva: World Health Organization.WHO Technical Report Series 894; 2000.

3.

Stuart RB. Behavioral control of overeating. BehavRes Ther. 1967;5:357-365.

4.

Foreyt JP, Goodrick GK. Factors common to successfultherapy for the obese patient. Med Sci SportsExerc. 1991;23:292-297.

5.

Wing RR. Behavioral approaches to the treatmentof obesity. In: Bray GA, Bouchard C, James WPT,eds. Handbook of Obesity. New York: Marcel DekkerInc; 1998:855-873.

6.

Epstein LH, Valoski A, Wing RR, McCurley J.Ten-year follow-up of behavioral, family-based treatmentfor obese children. JAMA. 1990;264:2519-2523.

7.

Heshka S, Greenway F, Anderson JW, et al. Selfhelpweight loss versus a structured commercialprogram after 26 weeks: a randomized controlledstudy. Am J Med. 2000;109:282-287.

8.

Freedman MR, King J, Kennedy E. Popular diets:a scientific review. Obes Res. 2001;9(suppl 1):1S-40S.

9.

Bray GA, Popkin BM. Dietary fat intake does affectobesity! Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:1157-1173.

10.

Bray GA, Lovejoy JC, Most-Windhauser M, et al.A nine-month randomized clinical trial comparing afat-substituted and fat-reduced diet in healthy obesemen: The Ole Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002. In press.

11.

Jenkins DJ, Jenkins AL, Wolever TM, et al. Lowglycemic index: lente carbohydrates and physiologicaleffects of altered food frequency. Am J Clin Nutr.1994;59(suppl 3):706S-709S.

12.

Saris W, Astrup A, Prentice AM, et al. Randomizedcontrolled trial of changes in dietary carbohydrate/fat ratio and simple vs complex carbohydrateson body weight and blood lipids: the CARMEN study.Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1310-1318.

13.

Roberts SB. High-glycemic index foods,hunger, and obesity: is there a connection? Nutr Rev.2000;58:163-169.

14.

Salmeron J, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Dietaryfiber, glycemic load, and risk of nonâinsulin-dependentdiabetes mellitus in women. JAMA. 1997;277:472-477.

15.

Zemel MB, Shi H, Greer B, et al. Regulation of adiposityby dietary calcium. FASEB J. 2000;14:1132-1138.

16.

Davies KM, Heaney RP, Recker RR, et al. Calciumintake and body weight. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.2000;85:4635-4638.

17.

Blair SN, Kampert JB, Kohl HW 3rd, et al. Influencesof cardiorespiratory fitness and other precursorson cardiovascular disease and all-causemortality in men and women. JAMA. 1996;276:205-210.

18.

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, etal. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabeteswith lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl JMed. 2002;346:393-403.

19.

McGuire MT, Wing RR, Klem ML, et al. Whatpredicts weight regain in a group of successfulweight losers? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:177-185.

20.

Bray GA, Greenway FL. Current and potentialdrugs for treatment of obesity. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:805-875.

21.

James WP, Astrup A, Finer N, et al, for theSTORM Study Group. Effect of sibutramine onweight maintenance after weight loss: a randomisedtrial. Sibutramine Trial of Obesity Reduction andMaintenance. Lancet. 2000;356:2119-2125.

22.

Bray GA, Blackburn GL, Ferguson JM, et al.Sibutramine produces dose-related weight loss. ObesRes. 1999;7:189-198.

23.

Bach DS, Rissanen AM, Mendel CM, et al. Absenceof cardiac valve dysfunction in obese patientstreated with sibutramine. Obes Res. 1999;7:363-369.

24.

Sjostrom L, Rissanen A, Andersen T, et al, forthe European Multicentre Orlistat Study Group.

Randomized placebo-controlled trial of orlistat forweight loss and prevention of weight regain inobese patients. Lancet. 1998;352:167-172.

25.

Rossner S, Sjostrom L, Noack R, et al, for theEuropean Orlistat Obesity Study Group. Weightloss, weight maintenance, and improved cardiovascularrisk factors after 2 years treatment with orlistatfor obesity. Obes Res. 2000;8:49-61.

26.

Davidson MH, Hauptman J, DiGirolamo M, etal. Weight control and risk factor reduction in obesesubjects treated for 2 years with orlistat: a randomizedcontrolled trial. JAMA. 1999;281:235-242.

27.

Hauptman J, Lucas C, Boldrin MN, et al. Orlistatin the long-term treatment of obesity in primarycare settings. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:160-167.

28.

Astrup A, Breum L, Toubro S, et al. The effectand safety of an ephedrine/caffeine compoundcompared to ephedrine, caffeine and placebo inobese subjects on an energy restricted diet: a doubleblind trial. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1992;16:269-277.

29.

Boozer CN, Daly PA, Homel P, et al. Herbalephedra/caffeine for weight loss: a 6-month randomizedsafety and efficacy trial. Int J Obes RelatMetab Res. 2002;26:593-604.

30.

Sjostrom CD, Lissner L, Wedel H, Sjostrom L.Reduction in incidence of diabetes, hypertensionand lipid disturbances after intentional weight lossinduced by bariatric surgery: the SOS InterventionStudy. Obes Res. 1999;7:477-484.

31.

Age-adjusted prevalence of overweight and obesityamong U.S. adults, age 20-74 years. Available at:

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/images/obsefig2.gif

. AccessedMay 31, 2002.

32.

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kuczmarski RJ, JohnsonCL. Overweight and obesity in the UnitedStates: prevalence and trends, 1960-1994. Int J ObesRelat Metab Disord. 1998;22:39-47.

33.

Rossner S. Factors determining the long-termoutcome of obesity treatment. In: Bjorntorp P, BrodoffBN, eds. Obesity. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1992:716.

34.

Pi-Sunyer FX, Becker DM, Bouchard C, et al.Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation,and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults.Washington, DC: NHLBI Obesity Education InitiativeExpert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation,and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity inAdults; 1998. US Dept of Health and Human Servicespublication NIH 98-4083:61.

35.

Jain AK, Kaplan RA, Gadde KM, et al. A study ofbupropion SR compared to placebo in obese adultswith mild to moderate depressive symptoms. Presentedat: 2001 Meeting of the North American Associationfor the Study of Obesity; October 7-10,2001; Quebec.

36.

Rosenfeld WE. Topiramate: a review of preclinical,pharmacokinetic, and clinical data. Clin Ther.1997;19:1294-1308.

37.

McElroy SL, Suppes T, Keck PE, et al. Openlabeladjunctive topiramate in the treatment of bipolardisorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:1025-1033.

38.

Shapira NA, Goldsmith TD, McElroy SL. Treatmentof binge-eating disorder with topiramate: a clinicalcase series. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:368-372.

39.

Bray GA, Klein S, Levy B, et al. Topiramate producesdose-related weight loss in obese patients. Diabetes. 2002;51(suppl 2):A420-A421.

40.

Bray GA, Tartaglia LA. Medicinal strategies inthe treatment of obesity. Nature. 2000;404:672-677.