- Clinical Technology

- Adult Immunization

- Hepatology

- Pediatric Immunization

- Screening

- Psychiatry

- Allergy

- Women's Health

- Cardiology

- Pediatrics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology

- Pain Management

- Gastroenterology

- Infectious Disease

- Obesity Medicine

- Rheumatology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Pulmonology

Fever and Rash: Infection or Kawasaki Syndrome?

Kawasaki syndrome (KS) is a common and serious disorderthat most often affects children aged 1 to 8 years but mimicsa range of other diseases of childhood. Diagnosis of KS isbased on physical examination findings coupled with theexclusion of other causes. To provide optimal care for patients,it is important to be aware of the differential diagnosis of KS.We report a case of a 4-year-old boy who presented withpersistent fever and cervical lymphadenitis; later, mucousmembrane changes, rash, and conjunctival injectioncharacteristic of KS developed. [Infect Med. 2008;25:320-322]

Kawasaki syndrome (KS) is a common vasculitis seen in the pediatric population. It also is known as mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome, and the cause is unknown. Epidemiologically, it is similar to an infectious disease; it has a seasonal occurrence and has been implicated in epidemics. Clinically, it is a vasculitis unresponsive to antibiotics. KS develops in healthy children and is the most common cause of acquired cardiac disease in the developed world. Chronic cardiac complications develop in 20% to 25% of children with untreated KS, and the most common and dangerous cardiac complication is coronary artery dilatation. It may result in rupture of the arteries and exsanguination. KS also may cause children to experience a prolonged course of arthritis, arthralgias, and crampy abdominal pain. Therefore, it is very important that KS is diagnosed accurately and treated appropriately and that clinicians are diligent about follow-up.

Case report

A 4-year-old boy with a past medical history of recurrent otitis media initially presented with a complaint of right ear pain and fever. Otitis media of the right ear was diagnosed, and amoxicillin therapy was begun. Four days later, the patient presented to his primary care physician because of persistent fever and enlargement of a left anterior cervical node. The ear pain had resolved, however. The patient was not taking in an adequate amount of fluids and thus was mildly dehydrated.

The patient's temperature was 38.7C (101.6F). His right tympanic membrane was slightly red, with fluid behind it. His tonsils were more than 3 mm in diameter and were erythematous. He had an enlarged (2 cm in diameter) left anterior cervical node. His skin turgor was decreased and no rash was noted.

The patient was admitted with suspected retropharyngeal abscess and for receipt of intravenous fluids and further evaluation and therapy. Intravenous clindamycin was administered immediately. His initial laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 18,480/?L, with 53% polymorphonuclear cells, 30% lymphocytes, 11% monocytes, and 6% eosinophils. His hemoglobin level was 10.8 g/dL, and the platelet count was 370,000/?L. The C-reactive protein level was 27 mg/L.

A CT scan of the neck showed no retropharyngeal abscess, but pansinusitis, bilateral middle ear opacification, and bilateral cervical adenopathy were evident. Further laboratory studies revealed an antistreptolysin O titer of less than 20 IU/mL, alanine aminotransferase level of 8 U/L, and aspartate amino-transferase level of 22 U/L. Test results were negative for Epstein-Barr virus and Parvovirus.

The patient remained febrile after 3 days of intravenous clindamycin therapy. On the third hospital day, a diffuse macular rash developed. The patient's lips were cherry red and dried, and his eyes were marked by a nonpurulent conjunctival injection. Cervical adenopathy was unchanged, and no swelling of the hands or feet occurred.

Findings on echocardiography were normal. The albumin level was 2.6 g/dL, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 78 mm/h. Intravenous clindamycin therapy was stopped, and the patient was given aspirin, 100 mg/kg/d, and intravenous immunogammaglobulin (IVIG), 2 g/kg.

Over the next 18 hours, the patient's condition rapidly improved. He became afebrile, his rash resolved, and his eyes and lips improved. He began to eat and drink normally, and the cervical adenopathy resolved. He was discharged home on the fifth hospital day with instructions to continue taking aspirin and to follow up with the pediatric infectious disease clinic in 1 week. At the follow-up visit, peeling of the hands and feet was observed. The patient continued to do well with no evidence of coronary abnormalities.

Discussion

The diagnosis of KS is defined by the presence of fever of at least 5 days' duration and 4 of the 5 following characteristics: conjunctival hyperemia, mucous membrane changes, distal extremity changes, polymorphous exanthema, and cervical adenopathy. The fever characteristic of KS is high and spiking. It is not affected by antibiotics or antipyretics and resolves within 24 to 48 hours of IVIG therapy. The onset of fever is considered the first day of the illness, from which all other events are measured.1

The conjunctival hyperemia seen in KS is characteristically nonexudative and is most apparent in the bulbar conjunctiva, with sparing of the limbic region around the iris. Hyperemia is noticeable a few days after the onset of fever and may persist for 1 to 2 weeks if left untreated.

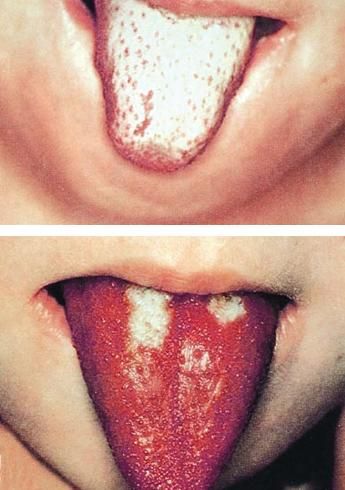

Effects of KS on mucous membranes are extensive and include diffuse erythema of the oral and pharyngeal mucosa without discrete ulcerative lesions. The lips also may be injected, dried, or fissured, and the patient may have a strawberry tongue (Figure 1).

These images illustrate the characteristic white(top) and red (bottom) strawberry tongue seen in Kawasakisyndrome.

The distal extremity changes of KS are progressive and include erythema of the palms and soles along with indurative edema of the hands and feet. Periungual desquamation (Figure 2) of the fingers and toes follows the swelling and is noticed on days 10 to 25. Beau lines (transverse grooves across the fingernails) may appear 2 to 3 months after disease onset.

Periungualdesquamation followsswelling in Kawasakisyndrome, as seen hereon a child's fingertips.

The polymorphous exanthema of KS is characterized by macules and papules without any vesicle or bullae formation. It is prominent on the trunk and extremities. In two-thirds of cases, it is accentuated in the perineal area (Figure 3). Fever and sore throat manifest 2 to 5 days before the rash appears, and the rash fades without residua within 10 days.

Perineal accentuationof exanthema occurs in two-thirdsof cases of Kawasaki syndrome.

The least prominent sign of KS is cervical adenopathy, which is present in about 50% of children with KS (other signs and symptoms discussed are present in about 90% of patients). This cervical adenopathy is characterized by an erythematous, indurated, nonsuppurative anterior cervical node of at least 1.5 cm in diameter (Figure 4).

Cervical adenopathy,characterized by an erythematous,indurated, nonsuppurative anteriorcervical node of at least 1.5 cm indiameter, is less prominent thanother signs or symptoms of Kawasakisyndrome. Nevertheless, it occursin up to 50% of affected children.

Additional characteristics of KS include constitutional symptoms (irritability, fatigue, and anorexia), GI symptoms (abdominal pain with or without vomiting and diarrhea, hepatic dysfunction with possible hydrops of the gallbladder, and pancreatitis), skeletal symptoms (arthritis or tympanitis with possible hearing loss), and lymphoid symptoms (exudative tonsillitis).

Laboratory abnormalities may include an elevated ESR or increases in other acute phase reactants, elevated transaminase levels, thrombocytosis, and hypoalbuminemia.

References:

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Summaries of infectious diseases. In: Pickering LK, ed. RedBook: 2003 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 27th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2006:412-415.