- Clinical Technology

- Adult Immunization

- Hepatology

- Pediatric Immunization

- Screening

- Psychiatry

- Allergy

- Women's Health

- Cardiology

- Pediatrics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology

- Pain Management

- Gastroenterology

- Infectious Disease

- Obesity Medicine

- Rheumatology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Pulmonology

Emerging Pathogens and New Recommendations in Travel Medicine

Most travelers to third-world countries encounter healthrelatedproblems during their stay and may require medicalattention on returning home. Although malaria is still themost common diagnosis among travelers to the developingworld, several other infectious diseases, such as avian influenza,dengue fever, chikungunya fever, leishmaniasis, andmultidrug-resistant tuberculosis, are growing in importance.Clinicians need to stay informed about travel requirementsand vaccine recommendations for US citizens. [Infect Med.2008;25:352-386]

More than half of travelers to the developing world experience a health-related problem during their trip, with 8% requiring medical attention on their return because of persistent symptoms. 1 The GeoSentinel database, a collaborative effort among 31 travel medicine clinics on 6 different continents, suggests that the most common diagnoses in these persons continue to be malaria (24%), dengue fever (6%), acute traveler's diarrhea (4%), and typhoid fever (2%).2

In recent years, however, the changing epidemiology of several pathogens has posed new risks to travelers. Among these are avian influenza, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection (ie, chikungunya fever), leishmaniasis, and dengue fever (DF). These emerging infections and new travel requirements and vaccine recommendations are summarized in this article.

Avian influenza

Influenza A virus of the H5N1 subtype, now known as avian influenza virus, is carried globally by wild birds and has caused significant morbidity and mortality among domesticated birds such as chickens, ducks, and turkeys. According to the World Bank, in Southeast Asia alone, avian influenza outbreaks since 2003 have resulted in the death or destruction of more than 140 million birds at a cost of more than $10 billion.3

Human cases of avian influenza are uncommon but have been reported since 1996. From 2003 to 2008, 369 human cases occurred in Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East, resulting in 234 deaths (63% of cases).4,5 Most cases occurred in previously healthy children and young adults aged 10 to 19 years who had direct or close contact with H5N1-infected poultry or contaminated surfaces. In general, the H5N1 strain does not easily infect humans. It is difficult for it to spread from person to person, and prolonged contact is usually required for transmission to occur. For instance, in Thailand in 2004, probable transmission occurred between an ill child and her mother, and in June 2006 in Indonesia, 8 persons were infected in one family.

Although person-to-person transmission remains very limited,6 scientists are concerned that the H5N1 virus could one day gain the ability to infect humans and easily spread from one person to another. With little to no immune protection in the human population, a worldwide influenza pandemic could result.

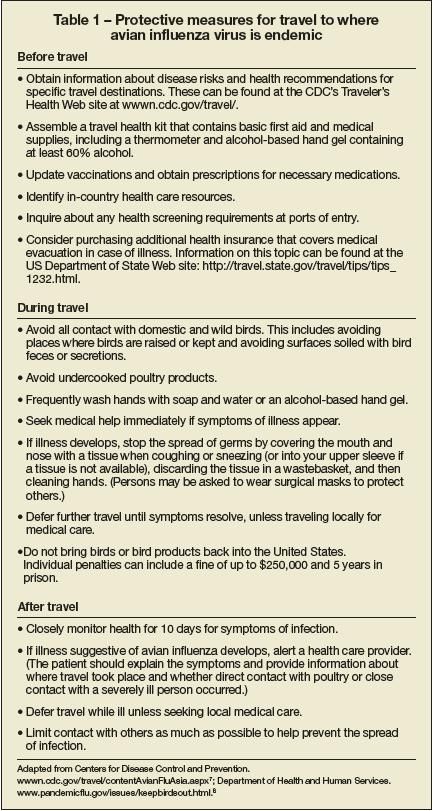

Currently, the CDC does not recommend that the general public avoid travel to countries affected by the H5N1 virus. However, it does recommend protective measures before, during, and after travel to regions where H5N1 is endemic (Table 1).7,8

Table 1

Table

Clinicians should alert travelers to the signs and symptoms of avian influenza. They include not only typical symptoms of influenza but also conjunctivitis; GI symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea; and occasionally neurological changes consistent with encephalitis. 6,9,10 Travelers should be instructed to seek medical care immediately if these signs and symptoms develop while they are traveling in a region where avian influenza is endemic or when they return home.

No vaccine is available to the general public to prevent avian influenza, although the FDA approved an H5N1 vaccine in April 2007 to be placed in national stockpiles in the event of an avian influenza pandemic. 11 Likewise, no antiviral agent has guaranteed efficacy. Human strains of avian influenza virus have largely been resistant to amantadine and rimantidine. Oseltamivir and zanamivir demonstrate some efficacy, but data are limited and oseltamivir resistance has been reported.6,12

Currently, experts advise clinicians against routinely providing oseltamivir to persons who are traveling to regions where avian influenza is endemic. Travelers should be alerted to the potential health risks posed by counterfeit supplies of antiviral drugs that are available on the Internet or in countries with lax drug production and distribution regulations.13

Although 59 cases of suspected avian influenza were reported to the CDC between 2003 and 2006, on laboratory analysis, none were confirmed. 14 In addition, no cases of avian influenza have been reported among international adoptees; however, the possibility exists, and like travelers, families preparing to adopt a child from abroad should be alerted to the signs and symptoms of avian influenza.15

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosisMycobacteria tuberculosis infects one third of the world's population, and 8 million new cases of TB and 2 million associated deaths occur each year. TB is second only to HIV infection as a cause of death worldwide from a single infectious agent. TB risk among international travelers is well documented, especially among those who are visiting Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the former Soviet Union.16

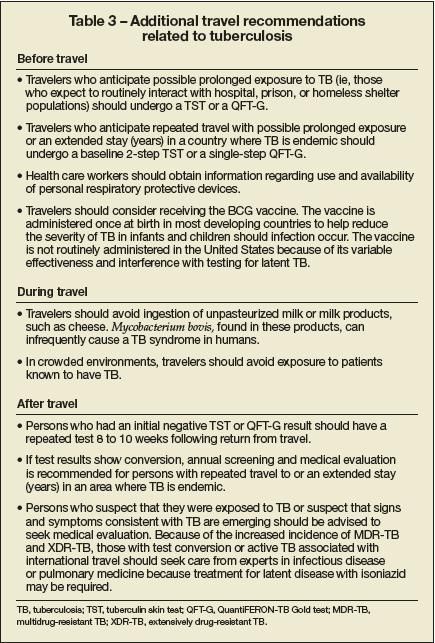

Media attention has recently focused on the acquisition of TB during air travel after a person with MDR-TB boarded an international flight against medical advice. First reports of TB transmission occurring in flight surfaced in the early 1990s, prompting the World Health Organization (WHO) to publish guidelines in 1998 for TB prevention and management during air travel. These guidelines were revised in 2006 in response to the increase in MDR-TB and the emergence of extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB).17 MDRTB is defined as M tuberculosis infection that is resistant to isoniazid and rifampin, whereas XDR-TB is defined as resistance to isoniazid, rifampin, any fluoroquinolone, and at least 1 of 3 injectable second-line drugs (ie, amikacin, kanamycin or capreomycin).18

WHO guidelines state that short flights pose minimal risk of disease transmission, but flights of more than 8 hours may put passengers at increased risk, similar to the risk of TB transmission in other confined spaces. The highest risk is to those in proximity to the index case and is primarily limited to persons seated in the same row, to those 2 rows ahead or behind, and to crew-members working in the same cabin area as the index case. Physicians who counsel patients regarding international travel should familiarize themselves with these guidelines, especially as they pertain to physician responsibilities (Table 2).17

Table 2

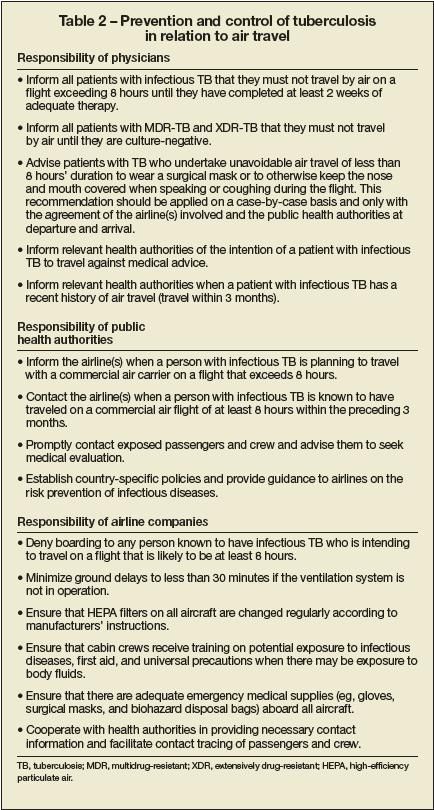

Greater than the risk of TB acquisition during international air travel is the risk of TB acquisition while visiting a country where the disease is endemic. Although the risk to short term travelers is low, the risk to longterm travelers to countries with a high incidence of TB may approach that of the local population and is especially high among health care workers. In a Dutch study of M tuberculosis infection among travelers to areas where the prevalence of TB is high, the risk of infection was 2.8 per 1000 person-months of travel for non-health care workers and 9.8 per 1000 person-months of travel for those with direct patient contact.19 Travel recommendations related to screening, prevention, and management of tuberculosis are outlined in Tables 2 and 3.20

Chikungunya fever

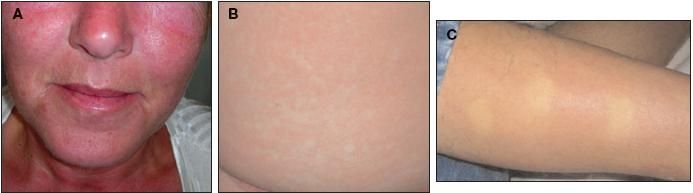

CHIKV, an arbovirus transmitted by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, was first identified in Tanzania in 1953.21 Chikungunya is derived from the local word "kungunyala" meaning "contorted," and refers to the severe joint pain experienced by infected patients.22 Acute infection is characterized by fever; headache; myalgias; and a subacute, bilateral polyarthralgia that typically affects the distal joints of the fingers, toes, ankles, and wrists.23 Rash is frequently observed; among 47 French patients returning from the Indian Ocean islands with CHIKV infection, 24 noted an evanescent pruritic rash over the face, trunk, or extremities accompanied by edema (Figure 1).24 Among 46 persons in this group of travelers, less common clinical manifestations were bilateral conjunctivitis in 2 patients (4%) and large joint effusions in 7 patients (15%). Common laboratory findings include elevation of liver and muscle enzyme levels, mild thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia.

Figure 1 -

Clinical manifestationsof chikungunya fever includea blanching, evanescentrash (A, B) and peripheraledema (C). (From Simon F et al.Medicine [Baltimore].200724; used withpermission.)

Hematological abnormalities in the acute phase may be associated with bleeding. Affected patients may suffer from a protracted illness characterized by persistent polyarthralgias and a limited ability to perform activities of daily living. Tenosynovitis also may exacerbate these latestage symptoms.24,25

Initially limited to Africa and Southeast Asia, CHIKV has recently spread to territories in the western and eastern Indian Ocean and India.26 In 2006, outbreaks of chikun- gunya fever in the Indian Ocean islands were attributed to an emerging vector, Aedes albopictus.27 Affected islands included the Comoros, Mauritius, the Seychelles, Madagascar, Mayotte, and Reunion. In Reunion, 265,000 clinical cases occurred among 770,000 inhabitants (34%), resulting in 237 deaths. That year, India reported an estimated 1.3 million cases28 and the global number of cases was close to 2 million.26 From 1991 to 2005, only 7 imported cases of CHIKV infection were identified in the United States, compared with 37 cases from 2005 through late September 2006.29

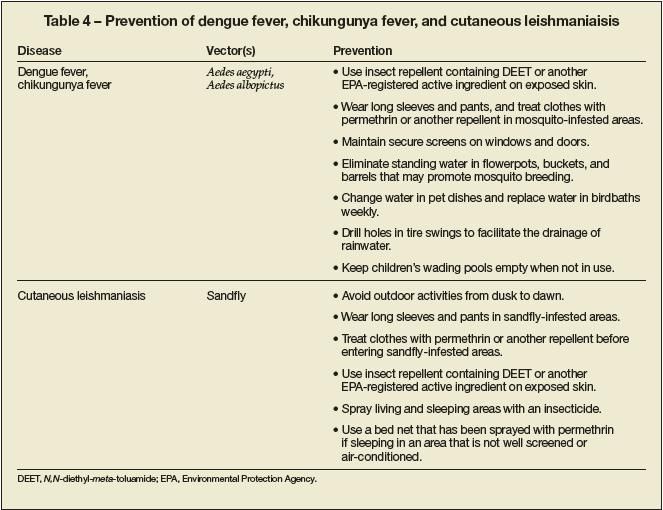

CHIKV infection should be a consideration in travelers with fever and arthralgias who have recently returned from areas where CHIKV is transmitted. Acute- and convalescent- phase serum specimens can be submitted to the CDC for testing through state health departments. Unfortunately, no vaccine or specific antiviral treatment exists. Therapy consists of supportive care, including rest, fluids, and antipyretics. Late-stage symptoms have demonstrated a dramatic response to short term corticosteroid therapy. The CDC suggests that infected persons should be protected from further mosquito exposure by staying indoors or under a mosquito net during the first few days of illness, thus limiting propagation of the transmission cycle.30 Recommendations for prevention are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4

Cutaneous leishmaniasisLeishmania species are intracellular protozoal parasites transmitted by the sandfly, most often in a rural setting. A wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, such as ulcerative skin lesions, mucocutaneous involvement, and visceral disease (kala azar) exist and are characterized as either Old World (southern Europe, Middle East, Asia, and Africa) or New World (Latin America). Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is endemic to more than 70 countries, with 90% of cases occurring in Afghanistan, Algeria, Brazil, Pakistan, Peru, Saudi Arabia, and Syria.31 Global incidence is increasing, with an estimated 1.5 to 2 million new cases each year, resulting in more than 70,000 deaths.32

Travel to regions of Central and South America where Leishmania is endemic has resulted in an increasing number of imported cases of New World CL in Europe. Between 1995 and 2003, the number of cases increased 3-fold in the United Kingdom. Similarly, between 1990 and 2000, the number of imported cases doubled in the Netherlands.31 Old World CL, most often associated with Leishmania major or Leishmania tropica, has been identified among US military personnel deployed to Afghanistan, Iraq, and Kuwait.33 From June 2003 to April 2004, more than 600 cases of Old World CL were diagnosed among American soldiers participating in Operation Iraqi Freedom. When cultures could be obtained (n = 308) from biopsies of skin lesions, L major was the pathogen in 99% of cases.34

CL is a chronic disease with lesions appearing within 1 to 7 months of exposure.5 Typically, an initial lesion develops at the site of the sandfly bite as a small, erythematous papule. Progressive ulceration follows within 2 weeks to 6 months of infection. Ulcerated lesions are typical of infection caused by New World species and L major (Figure 2). More severe cutaneous disease may spread locally or hematogenously to involve deeper tissues. In Latin America, most such cases are caused by Leishmania braziliensis and Leishmania amazonensis.35

Figure 2 -

New World cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania major is characterizedby painless, well-demarcated ulcers at the site of sandfly bites.

A detailed review of therapeutic options for CL has been provided elsewhere.31 Intralesional and parenteral pentavalent antimonials- sodium stibogluconate and meglu-mine antimoniate-have been used successfully, but serious adverse effects, such as myalgias, renal failure, hepatotoxicity, and cardiotoxicity, may occur.36 In the United States, sodium stibogluconate is available for parenteral use under an investigational drug protocol by contacting the CDC (404-639-3670). Alternative treatment regimens have met with varying success, including amphotericin B and its lipid formulations, pentamidine, and miltefosine.31 Oral azoles (eg, ketoconazole, fluconazole), topical agents (eg, paromomycin cream), and thermotherapy have also been used. Personal protection against sandflies is necessary for travelers.37 The CDC recommendations for prevention are detailed in Table 4.

Dengue fever

DF and dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) are caused by 4 related but antigenically distinct dengue virus serotypes of the virus family Flaviviridae. DF is a self-limited disease characterized by the sudden onset of fever, severe headache, myalgias, and arthralgias, which are often accompanied by a maculopapular rash. DHF is a more severe disease with a mortality rate between 1% and 50% in developed and developing countries, respectively.38 It occurs 4 to 7 days after dengue virus infection and is heralded by capillary leakage and hemorrhagic complications. Neutropenia, elevated liver enzyme levels, and disseminated intravascular coagulation are also common. One of the most important risk factors for DHF is previous dengue virus infection.39 Therefore, the risk to first-time international travelers from areas where the disease is not endemic is low, but the risk increases with subsequent travel.

The primary vector of dengue virus is A aegypti, although infection associated with A albopictus40 also has been reported. Most cases of DF and DHF have been reported in Asia, but in the late 1980s and early 1990s, epidemics occurred in Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands, the Caribbean, and Latin America.41 Over the past few years, DF has become endemic to most tropical countries of the South Pacific, Asia, the Caribbean, the Americas, and Africa.

Dengue virus is the most common cause of arboviral disease in the world, accounting for 50 million to 100 million cases and more than 22,000 deaths annually.42 The marked increase in DF over the past 2 decades in areas where the disease is endemic also has resulted in increased infection rates among travelers. DF and DHF have been diagnosed in up to 16% of febrile travelers returning from the tropics, a 3-fold increase since 1990.43 From 1977 to 2004, 864 cases of DF were reported in the United States among returning travelers.44 Rarely, these infected travelers can serve as a source for DF transmission when returning to an A aegypti-infested or A albopictus-infested area. This phenomenon was demonstrated in Hawaii in 2001, when the arrival of a single viremic traveler from the South Pacific resulted in a limited local outbreak.45

A aegypti, a daytime feeder, is found most frequently in or near human habitations. Mosquito breeding sites include artificial water containers, such as discarded tires, uncovered water storage barrels, buckets, and cisterns. Extensive public health measures have been taken to limit these potential breeding sites. For travelers, the most effective preventive measure is the use of insect repellents containing N,N-diethylmeta- toluamide (DEET) and permethrin- impregnated protective clothing. 46 Because the transmission risk is highest during the day, the utility of bed nets at night is limited. Travelers to areas where DF is endemic and epidemic should take precautions to avoid mosquito bites as detailed in Table 4.

Travel requirements and vaccine recommendations

In 2008, yellow fever vaccination requirements expanded to travelers to Costa Rica, Argentina, Paraguay, Bo- livia, and Brazil. Specifics may be obtained by reviewing The Yellow Book, CDC Health Information for International Travel 2008 (available on the Web at http://wwwn.cdc.gov/ travel/contentYellowBookUpdates. aspx).47 A new International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (ICVP) was issued in December 2007 and should be used to record yellow fever vaccine administration. Health care practitioners should replace older versions with the current ICVP whenever possible.

In October 2007, the tetravalent meningococcal polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccine (MCV4), conferring protection against Neisseria meningitidis serogroups A, C, Y, and W-135, was approved for use in children aged 2 to 10 years.48 The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends the use of meningococcal vaccine for persons who travel to or reside in countries in which N meningitidis is hyperendemic or epidemic, particularly if contact with the local population will be prolonged. MCV4 is preferred and may now be used among persons aged 2 to 55 years. MPSV4, a tetravalent meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine, remains the recommended vaccine among persons older than 55 years who travel to regions in which N meningitidis is prevalent.49

In 2006, an outbreak of mumps in the United States prompted revised recommendations for vaccination. Presently, according to the ACIP, adequate mumps vaccination for international travelers now consists of 2 doses of live virus vaccine instead of 1 dose.50

Routine vaccination guidelines for adults have been updated to include herpes zoster vaccination of persons 60 years and older who do not have evidence of past varicella immunity. Evidence of past varicella immunity is described in the 2008 ACIP Adult Immunization Schedule. 51 All adults without evidence of immunity to varicella should receive 2 doses of single-antigen herpes zoster vaccine unless a medical contraindication exists.

CONCLUSION

Because 40 million Americans travel or work abroad annually,

52

physicians should be prepared to provide pre-travel counseling for their patients. To provide comprehensive care, clinicians must maintain a working knowledge of emerging pathogens and travel vaccination recommendations. Travel medicine experts and dedicated Web sites maintained by the CDC and the WHO can provide additional valuable information.

References:

- Freedman DO, Weld LH, Kozarsky PE, et al; GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Spectrum of disease and relation to place of exposure among ill returned travelers [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2006;355:967]. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:119-130.

- Wilson ME, Weld LH, Boggild A, et al; GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Fever in returned travelers: results from the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1560- 1568.

- The World Bank. Economic impact of avian flu. http://go.worldbank.org/DTHZZF6XS0. Accessed March 20, 2008.

- World Health Organization. Cumulative number of confirmed human cases of avian influenza A/(H5N1) reported to WHO as of 28 February 2008. www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_ influenza/country/en/. Accessed March 3, 2008.

- World Health Organization. Areas with confirmed human cases of H5N1 avian influenza since 2003. http://gamapserver.who.int/ mapLibrary/app/searchResults.aspx. Accessed March 3, 2008.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Key facts about avian influenza (bird flu) and avian influenza A (H5N1) virus. www.cdc. gov/flu/avian/gen-info/facts.htm. Accessed March 3, 2008.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak notice. Human infection with avian influenza A(H5N1) virus: advice for travelers. wwwn.cdc.gov/travel/contentAvianFluAsia. aspx. Accessed June 13, 2008.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Keep bird flu out of the United States Poster. www.pandemicflu.gov/issues/keepbirdsout. html. Accessed March 4, 2008.

- Apisarnthanarak A, Kitphati R, Thongphubeth K, et al. Atypical avian influenza (H5N1). Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1321-1324.

- de Jong MD, Bach VC, Phan TQ, et al. Fatal avian influenza A(H5N1) in a child presenting with diarrhea followed by coma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:686-691.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first U.S. vaccine for humans against the avian influenza virus H5N1. www.fda.gov/ bbs/topics/NEWS/2007/NEW01611.html. Accessed March 3, 2008.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Questions and answers about avian influenza (bird flu) and avian influenza A(H5N1) virus. www.cdc.gov/flu/avian/gen-info/qa.htm. Accessed March 4, 2008.

- US Department of State. Avian flu fact sheet. http://travel.state.gov/travel/tips/health/ health_1181.html#. Accessed March 3, 2008.

- Ortiz JR, Wallis TR, Katz MA, et al. No evidence of avian influenza A(H5N1) among returning US travelers. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:294-297.

- Staat DD, Klepser ME. International adoption: issues in infectious diseases. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:1207-1220.

- Fitzgerald D, Haas DW. Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Bennett & Dolin: Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005:2852-2886.

- World Health Organization. Tuberculosis and air travel: guidelines for prevention and control. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006:1-43. www.who.int/ docstore/gtb/publications/aircraft/PDF/98_ 256.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2008.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR TB). www.cdc.gov/tb/pubs/tbfactsheets/mdrtb. htm. Accessed March 17, 2008.

- Cobelens FG, van Deutekom H, Draayer- Jansen IW, et al. Risk of infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis in travellers to areas of high tuberculosis endemicity. Lancet. 2000;356:461- 465.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tuberculosis. In: Arguin PM, Kozarsky PE, Reed C, eds. Health Information for International Travel 2008. Philadelphia: Elsevier, Inc; 2007. www.eid.ac.cn/MirrorResources/2966/ yellowBookCh4-TB.aspx.1.html. Accessed March 17, 2008.

- Robinson MC. An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952-53. I. Clinical features. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1955;49:28-32.

- Ross RW. The Newala epidemic. III. The virus: isolation, pathogenic properties and relationship to the epidemic. J Hyg (Lond). 1956;54:177- 191.

- Outbreak news. Chikungunya and dengue, south-west Indian Ocean. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2006;81:106-108.

- Simon F, Parola P, Grandadam M, et al. Chikungunya infection: an emerging rheumatism among travelers returned from Indian Ocean islands. Report of 47 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:123-137.

- Kennedy AC, Fleming J, Solomon L. Chikungunya viral arthropathy: a clinical description. J Rheumatol. 1980;7:231-236.

- Charrel RN, de Lamballerie X, Raoult D. Chikungunya outbreaks-the globalization of vectorborne diseases. N Engl J Med. 2007;356: 769-771.

- Laras K, Sukri NC, Larasati RP, et al. Tracking the re-emergence of epidemic chikungunya virus in Indonesia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99:128-141.

- Mudur G. Failure to control mosquitoes has led to two fever epidemics in India. BMJ. 2006;333: 773.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chikungunya fever diagnosed among international travelers-United States, 2005-2006. MMWR. 2006;55:1040-1042.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chikungunya fever fact sheet. www.cdc.gov/ ncidod/dvbid/Chikungunya/chikvfact.htm. Accessed March 19, 2008.

- Reithinger R, Dujardin JC, Louzir H, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007; 7: 581-596.

- WHO. The world health report 2004. Changing history. Geneva: WHO, 2004. www.who.int/ whr/2004/en/index.html. Accessed March 19, 2008.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in U.S. military personnel- southwest/central Asia, 2002-2003. MMWR. 2003;52:1009-1012.

- Weina PJ, Neafie RC, Wortmann G, et al. Old World leishmaniasis: an emerging infection among deployed US military and civilian workers. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1674-1680.

- Bailey MS, Lockwood D. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:203-211.

- Croft SL, Yardley V. Chemotherapy of leishmaniasis. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:319-342.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Health Information for International Travel 2008. wwwn.cdc.gov/travel/yelloBookCh4- Leishmaniasis.aspx. Accessed March 19, 2008.

- Tsai TF, Vaughn DW, Solomon T. Flaviviruses. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Bennett & Dolin: Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005.

- Rigau-Pérez JG, Clark GG, Gubler DJ, et al. Dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever. Lancet. 1998;352:971-977.

- Gubler DJ. The global emergence/resurgence of arboviral diseases as public health problems. Arch Med Res. 2002;33:330-342.

- Gubler DJ, Clark GG. Dengue/dengue hemorrhagic fever: the emergence of a global health problem. Emerg Infect Dis. 1995;1:55-57.

- WHO. Dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever. www.who.int.ezproxy.galter.northwestern. edu/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en/. Accessed March 19, 2008.

- Wilder-Smith A, Schwartz E. Dengue in travelers. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:924-932.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dengue fever. www.cdc.gov/NCIDOD/ DVBID/DENGUE/.Accessed March 19, 2008.

- Effler PV, Pang L, Kitsutani P, et al; Hawaii Dengue Outbreak Investigation Team. Dengue fever, Hawaii, 2001-2002. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005; 11:742-749.

- Fradin MS, Day JF. Comparative efficacy of insect repellents against mosquito bites. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:13-18.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updates to the Online Edition of The Yellow Book-CDC Health Information for International Travel 2008. wwwn.cdc.gov/travel/ contentYellowBookUpdates.aspx. Accessed on March 19, 2008.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notice to readers: recommendation from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for use of quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV4) in children aged 2-10 years at increased risk for invasive meningococcal disease. MMWR. 2007;56:1265- 1266.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notice to readers: revised recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices to vaccinate all persons aged 11-18 years with meningococcal conjugate vaccine. MMWR. 2007;56:794-795.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notice to readers: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for the control and elimination of mumps. MMWR. 2006;55:629-630.

- Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Recommended adult immunization schedule: United States, October 2007-September 2008. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:725-729.

- Reyes I, Shoff WH. General medical advice for travelers. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1997;15: 1-16.