- Clinical Technology

- Adult Immunization

- Hepatology

- Pediatric Immunization

- Screening

- Psychiatry

- Allergy

- Women's Health

- Cardiology

- Pediatrics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology

- Pain Management

- Gastroenterology

- Infectious Disease

- Obesity Medicine

- Rheumatology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Pulmonology

Differentiating Kawasaki Syndrome From Microbial Infection

Kawasaki syndrome is a serious disorder affecting children aged 1 to 8 years. It mimics a range of other diseasesof childhood. Diagnosis is based on physical examination findings coupled with the exclusion of other causes.

Kawasaki syndrome (KS), also known as mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome, the cause of which is unknown, is a common vasculitis seen in the pediatric population. Epidemiologically, it is similar to an infectious disease in that it has a seasonal occurrence and has been implicated in epidemics. Clinically, it is a vasculitis that is unresponsive to antibiotics. Two important aspects of KS are that it develops in healthy children and is the most common cause of acquired cardiac disease in the developed world. In fact, chronic cardiac complications develop in 20% to 25% of children in whom KS goes untreated. The most common and dangerous cardiac complication is coronary artery dilatation, which may result in rupture and exsanguination. Children also may experience a prolonged course of arthritis, arthralgias, and cramping abdominal pain. Therefore, it is very important to diagnose KS with certainty, treat it appropriately, and follow up patients meticulously.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES

Since there is no specific diagnostic test for KS, the diagnosis hinges on meeting 4 of the 5 criteria as well as the presence of fever for 5 days. Because the diagnostic features often have different presentations, the diagnosis of KS may be difficult even for the experienced clinician. Thus, it is always important to consider the differential diagnosis when confronted with a child in whom KS is suspected. KS should be considered in any child with fever for more than 5 days, especially if the child has a rash and nonpurulent conjunctivitis. The differential diagnosis of KS is extensive and includes bacterial and viral infections and rheumatological diseases, among other causes.

Bacterial infections

Bacterial infections that play into the differential diagnosis include scarlet fever; staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS); toxic shock syndrome (TSS); Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) and other forms of rickettsial infection, such as typhus; leptospirosis; rat-bite fever; and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection.1-10

Scarlet fever is a syndrome that results from erythrogenic exotoxin A production by group A Streptococcus. It is similar to KS in that it causes desquamation with time, including periungual desquamation. Infection also can cause cervical adenopathy, exudative tonsillitis, and strawberry tongue.

A few distinguishing features help differentiate scarlet fever from KS. Although a desquamating rash is a characteristic of both diseases, the rash associated with scarlet fever may become blanched. It is diffusely erythematous, resembling a sunburn, and is rough with a sand papertexture. The rash is most intense on the axillae and on the groin, abdomen,and trunk. It generally appears about 24 hours after the onset of fever. It is first seen on flexor surfaces of the extremities and becomes generalized in 24 to 48 hours. Pastia sign (Figure 1), nonblanching skin folds, and circumoral pallor also may be noted. Cephalic to caudal desquamation occurs about a week after the onset of rash. Finally, if physical findings are not sufficient to determine a diagnosis, checking antistreptolysin O titers can be helpful because levels may be elevated in patients with scarlet fever.

The appearance of Pastia sign helps distinguish scarlet fever from other causes of rash.

SSSS is another toxin-mediated disorder. It shares with KS the characteristics of a desquamating truncal rash and an erythematous, peeling, fissured "sunburst" rash around the mouth. Unlike KS, SSSS is preceded by an initial infection of the upper respiratory tract. Another distinguishing characteristic is that the rash of SSSS usually spares the palms, soles, and mucous membranes. The peeling is confined to areas around body orifices.

One to 2 days after the rash manifests, bullae may appear and exfoliate in sheets, which is referred to as a positive Nikolsky sign. Isolation of staphylococci from a site other than the blisters (eg, conjunctivae or nasopharynx) or from the blood will aid in the diagnosis.

TSS is generally caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Similarities between TSS and KS include edema of the face, palms, and soles. In addition, desquamation of the skin 1 to 2 weeks after illness onset, strawberry tongue, and bulbar conjuctival hyperemia are present in both illnesses.

Distinguishing characteristics of TSS include shock, a widespread blanching erythroderma eruption that is most prominent on the trunk and extremities, and possible subconjunctival hemorrhage (Figure 2). Approximately 85% of TSS patients have S aureus isolated from their mucosa or wound sites, but isolation of the organism is not required to make the diagnosis.

Subconjunctival hemorrhage may appear as a symptom of toxic shock syndrome (TSS). Its appearance helps distinguish TSS from Kawasaki syndrome.

RMSF, a rickettsial infection, is caused by the spirochete Rickettsia rickettsii. It is transmitted through the bite of a tick and is most prevalent in the southeastern and central Mississippi valley regions of the United States, with North Carolina and Oklahoma having the highest incidence. Similarities to KS include fever, maculopapular rash with involvement of palms and soles, and conjunctival hyperemia. In contrast to KS, RMSF causes a peripherally distributed eruption beginning on the ankles, wrists, and forehead, in which the initial lesions may blanch and appear as small red macules that rapidly progress to maculopapules and finally to petechiae. The onset of rash is preceded by a 3- to 7-day prodrome of chills, fever, and severe frontal headache, malaise, and anorexia. Thrombocytopenia, hyponatremia, elevated aminotransferase levels, hyperbilirubinemia, leukopenia, and coagulopathies might emerge. Serum antibodies reactive to R rickettsii may be detected by indirect immunofluorescence assay, but diagnostic levels might be undetectable until the second week after syndrome onset.

Febrile rickettsial infection includes epidemic and murine typhus, and it is transmitted by fleas or lice harboring Rickettsia species. Similarities to KS include high fever, a maculopapular petechial eruption, and cervical adenopathy. Some distinguishing characteristics include a 4- to 6-day prodrome with high fever,chills, headache, and generalized aches and pains. In addition, the maculopapular rash is often centrally distributed, and neuroretinitis may be found. The indirect fluorescent antibody test is often used to confirm the diagnosis.

Leptospirosis is caused by the spirochete Leptospira interrogans, which is transmitted by dogs, swine, rodents, and contaminated water. Similarities to KS include a maculopapular rash with peripheral desquamation, conjunctivitis, cervical lymphadenopathy, and pharyngitis. One of the distinguishing characteristics is conjunctivitis with episcleral injection and uveitis that may be unilateral or bilateral and usually involves the entire uveal tract. The rash is maculopapular to generalized and may be petechial or purpuric. Erythema nodosa also may be noted.

The anicteric form of leptospirosis is the most common form and is associated with biphasic fever, myalgias, and chills. Acalculous cholecystitis or intense jaundice is occasionally seen in children. Laboratory studies that may aid in the diagnosis include those that evaluate for leukocytosis, hematuria, proteinuria, azotemia, and hyperbilirubinemia.

Rat-bite fever is a very rare syndrome caused by either Spirillum minus or Streptobacillus moniliformis. Similarities to KS include intermittent fever, rash on the palms and soles, and lymphadenopathy. It has many distinguishing characteristics, including a waxing and waning pattern of fever of 3 to 4 days' duration alternating with afebrile periods lasting 3 to 9 days; this cycle may persist for weeks. The rash often develops 1 to 8 days after fever onset. Laboratory tests may indicate leukocytosis and may yield false-positive results for venereal diseases.

Y pseudotuberculosis is transmitted by the ingestion of incompletely cooked pork, unpasteurized milk, or contaminated well water or by indirect contact with infected animals. This bacterium causes a fever, rash, lymphadenitis, and conjunctivitis similar to those seen with KS. Some distinguishing characteristics of Y pseudotuberculosis infection include varying degrees of fever, a scarlatiniform rash, and mesenteric adenitis (which may mimic acute appendicitis). It is also associated with Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome, which includes unilateral conjunctivitis with conjunctival granulomas, ptosis, preauricular adenopathy, photophobia, and external signs of inflammation. Of interest, 75% of patients with clinically apparent Y pseudotuberculosis infection are children younger than 15 years.

Viral infections

Viral infections that are symptomatically similar to KS include adenovirus infections as well as measles, German measles, roseola infantum, erythema infectiosum, and mononucleosis.1,2,4-7

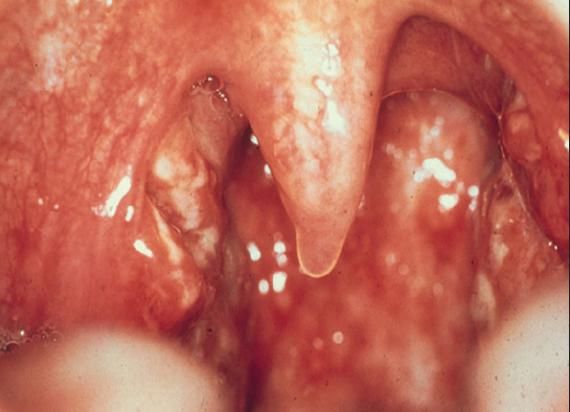

Adenovirus infections, like KS, are characterized by a persistent high fever, pharyngitis (Figure 3), conjunctivitis, cervical lymphadenopathy, and rash.

Pharyngeal manifestations, including erythema, tonsillitis, and exudates, also are indicative of adenovirus infection.

Distinguishing characteristics of adenovirus infections include sore throat, rhinitis, and unilateral conjunctivitis that can include serous discharge, subconjunctival hemorrhages, and the formation of a grayish pink friable membrane on the palpebral conjunctiva. The conjunctivitis also is associated with an itching, burning, foreign-body sensation that is not seen in KS.

The discrete generalized erythematous maculopapular rash of adenovirus infections often appears while the child is febrile. Adenoviruses also can cause right iliac fossa abdominal pain. Direct antigen testing or viral culture can be used to detect adenoviruses.

Measles, caused by the rubeola virus, shares similarities with KS in that it is characterized by swelling of the hands and feet, a maculopapular rash with desquamation, conjunc-tivitis, and fever that persists for 5 to 7 days. Some unique characteristics of measles include a 3- to 4-day prodrome of fever, conjunctivitis, coryza, and severe cough. In contrast to KS, the conjunctivitis of measles is exudative. The brick-red rash of rubeola starts on the face, the neck, and behind the ears; it then extends down the trunk and onto the extremities. The rash is initially maculopapular and becomes more confluent before it begins to fade after 3 days, leaving behind a distinctive brownish hue. This is often followed by a branny desquamation that does not involve the hands and feet. In addition, Koplik spots on the buccal mucosa and a central, white coating of the tongue with an erythematous tip and margins may be seen.

Similarities between KS and German measles, which is caused by the rubella virus, include a maculopapular rash, adenopathy, and fever. German measles is distinguished from KS by a nonspecific prodrome of fever, coryza, sore throat, arthralgias, and adenopathy that occurs 1 to 5 days before exanthem onset, but this is more common in adolescents and adults than in infants and young children.

The rash is characterized by a nondesquamating, pale pink, morbilliform maculopapular eruption that begins on the face and neck and progresses down the trunk to the extremities. The rash is generalized in 24 to 48 hours, lasts 1 day in each area, and fades rapidly. In addition to cervical adenopathy, postauricular and occipital lymphadenopathy and arthralgias also may be noted.

Roseola infantum is caused by human herpesvirus 6 and usually occurs in children aged 6 to 36 months. It is characterized by persistent fever of 3 to 5 days' duration, followed by rash and lymphadenopathy. Distinguishing features of roseola infantum include an erythematous and morbilliform rash that consists of rose-colored macules appearing on the neck, trunk, and buttocks and less frequently on the face and extremities that begins as the fever abates. The mucous membranes are often spared, and the rash resolves in 1 to 2 days. Patients with roseola infantum also are at increased risk for febrile convulsions. Laboratory studies often show leukopenia.

Erythema infectiosum (also called fifth disease) is caused by Parvovirus B19. Like KS, it is characterized by fever, adenopathy, and rash. Unlike KS, a prodrome of malaise, pharyngitis, coryza, and fever precedes the illness. The characteristic "slapped cheek" rash generally follows about 10 days later. In the second phase of the illness, the rash spreads to extremities and becomes symmetrical, morbilliform, and lacelike or annular with central clearing and is often mildly pruritic. It spares the mucous membranes, palms, and soles. In its final phase, the rash may remit and recur for weeks with stress, exercise, or bathing. Complications of erythema infectiosum include arthritis, hemolytic anemia, aplastic crisis, and nonimmune hydrops in the fetus and newborn.

Mononucleosis is caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Similarities to KS include fever, rash, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Mononucleosis is typically characterized by a triad of membranous tonsillitis with or without exudates, cervical lymphadenopathy, and splenomegaly. The rash of mononucleosis is rare (5% to 10% of patients with EBV infection) and may appear as 2 different exanthems. The first type of exanthem is erythematous, maculopapular, and rubella-form and is more prominent on the trunk and proximal upper extremities (occasionally it is seen on the face, forearms, and legs). This is the classic, non-antibiotic-related EBV rash. The second type is an erythematous or copper-colored ampicillin-associated rash that begins on the trunk and spreads to the face and extremities. EBV infection can be diagnosed in the clinic with the monospot test or with specific EBV antibody tests.

Rheumatological diseases

A few rheumatological diseases cause symptoms similar to those of KS, including Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, Henoch-Schnlein purpura (HSP), and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA).8

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, an infantile, papular acrodermatitis originally associated with hepatitis B surface antigen that may occur after viral infection, is caused by pathogens such as EBV, cytomegalovirus, enteroviruses, and respiratory syncytial virus. Like KS, this syndrome includes a desquamative rash and lymphadenopathy. The rash is characterized by a sudden eruption of symmetric, flat-topped, discrete, nonpuritic, skin-colored to erythematous papules on the malar face, extremities, and buttocks (Figure 4) that spares the trunk, mucous membranes, and antecubital and popliteal fossae. The lesions then fade and desquamate spontaneously within 2 to 3 weeks but may remain for up to 8 weeks. The lymphadenopathy is generalized and inguinal, and maxillary nodes can be enlarged for 2 to 3 months after onset.

The rash associated with Gianotti-Crosti syndrome is desquamative like that of Kawasaki syndrome. However, it is uniquely characterized by a sudden eruption of symmetrical, flat-topped, discrete, nonpuritic, skin-colored to erythematous papules on the malar face, extremities, and buttocks.

HSP is a systemic vasculitis with deposition of IgA-containing immune complexes throughout the body. Like KS, HSP is characterized by fever; rapidly fading rash; swollen hands, feet, and periorbital areas; arthritis; and abdominal pain. Unlike KS, HSP is classically described as intermittent purpura, arthralgias, abdominal pain, and renal disease. HSP also may be preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection, mild fever, and headache.

The initial lesions are symmetrical, blotchy, erythematous macules that become urticarial and then purpuric within a day. The palpable purpuric lesions are seen on the buttocks, extensor surfaces of extremities, back, scrotum and, occasionally, the face.

In a child younger than 2 years, edema of the scalp, hands, feet, and periorbital tissues may develop before the appearance of purpuric lesions. Cutaneous hemorrhage may be the sole manifestation of any attack, with arthralgia and arthritis noted as a migratory, periarticular swelling of the knees and ankles. Patients also may have colicky abdominal pain associated with vomiting and melena, and mild renal involvement with transient proteinuria, hematuria, and focal glomerular involvement. Abnormal findings on laboratory tests include leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Skin biopsy specimens show IgA, C3, and fibrin deposits.

JRA has characteristics similar to those of KS, including lymphadenopathy, rash, and high, spiking fevers. These fevers are dramatic, with sweats and chills, and temperatures often spike to 40C (104F) before plunging to several degrees below normal (picket fence temperature). The rash is a transient, evanescent, salmon-colored, nonpruritic rash that is primarily noticeable on the chest and abdomen. It often appears and disappears with the fever spikes. Many patients may initially complain of mild sore throat and joint symptoms that become a progressively destructive arthritis primarily affecting the wrists. Hepatosplenomegaly during the rash, anemia, and leukocytosis also may be present.

Other differential diagnoses

Other syndromes with characteristics similar to those of KS include Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), acrodynia, and convulsant hypersensitivity syndrome (CHS).6,9,10

SJS is a condition caused by a severe allergic reaction to drugs such as sulfonamides, NSAIDs, and phenytoin and by infections such as those caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae and herpes simplex virus. Like KS, SJS is characterized by pharyngitis, fever, conjunctivitis, a maculopapular rash involving the hands and feet, and hemorrhagic lips. The rash tends to be vesicular with crusting of edematous, erythematous eruptions involving the face, hands, and feet. Bullous erythema multiforma, with lesions that may slough off as large pieces of skin, also may be noted. Stomatitis is an early and conspicuous symptom, beginning with vesicles on the tongue, lips, and buccal mucosa (Figure 5). This later becomes more severe and includes pseudomembranous exudation, excessive salivation, and ulcerations. Rhinitis with epistaxis and crusting of the nares also may be seen. The conjunctivitis of SJS is bilateral and often exudative. Laboratory testing may indicate an increased ESR, although the ESR is not as high as that seen in KS.

Stomatitis is an early symptom of Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and helps distinguish SJS from Kawasaki syndrome. Vesicles develop on the tongue, lips, and buccal mucosa. Extensive stomatitis, crusting, and erythematous eruptions are depicted here.

Acrodynia, also known as erythredema polyneuropathy or pink disease, is caused by mercury poisoning that usually occurs in infancy. Similar to KS, it is characterized by painful swelling of the hands and feet, a maculopapular rash, and irritability. Unlike KS, the erythema is blotchy and diffuse. Hands and feet also may be cold, clammy, pink or dusky red, and pruritic. In addition, hemorrhagic puncta may be seen. Laboratory studies may demonstrate albuminuria, hematuria, and the presence of mercury in urine.

CHS is a systemic reaction to anticonvulsant therapy. Like KS, it is characterized by fever, maculopapular rash, and lymphadenopathy. It includes involvement of visceral organs, and fulminant hepatitis may develop. The lymphadenopathy is generalized. The rash usually begins 2 to 8 weeks after the drug is begun and usually resolves when the drug is stopped. CHS may be followed by an eosinophilic colitis. Helpful findings from laboratory tests include leukocytosis with eosinophilia and a normal ESR.

TREATMENT

High-dose intravenous gamma globulin (IVIG) (2 g/kg) as a single dose along with high-dose aspirin (100 mg/kg/d) for 10 to 14 days followed by low-dose aspirin (5 mg/kg/d) until acute inflammatory mediators return to normal is the standard of care for KS.1 This therapy has been shown to reduce the incidence of coronary artery disease. The most serious complication associated with KS is a coronary artery aneurysm. Aneurysms may lead to sudden death, often within the first 30 days after the onset of KS. Usually IVIG is followed by a prompt end to most symptoms the child is having. On occasion, a second dose of IVIG is required. Any child whose status does not improve after a second dose of IVIG should be reevaluated.

References:

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Summaries of Infectious Diseases. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2003 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 27th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2006:412-415.

- Darmstadt GL, Marcy SM. Erythematous macules and papules. In: Long SS, Pickering LK,Prober CG, eds. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2003:432-434.

- Gomez HF, Cleary TG. Yersinia species. In: Long SS, Pickering LK, Prober CG, eds. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2003: 839-843.

- Demmler GL. Adenoviridae. In Long SS, Pickering LK, Prober CG, eds. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2003:1076-1080.

- Maldonado YA. Rubeola virus. In: Long SS, Pickering LK, Prober CG, eds. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2003:1148- 1155.

- Cohen BA, ed. Pediatric Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005:161-200.

- Davis HW, Michaels MG. Infectious disease. In: Zitelli BJ, Davis HW, eds. Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis. 4th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 2002:396-454.

- McIntire SC, Urbach AH, Londino Jr AV. Rheumatology. In: Zitelli BJ, Davis HW, eds. Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis. 4th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 2002:225-256.

- Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention American Academy of Pediatrics. Handbook ofCommon Poisonings in Children. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 1994:216-219.

- Le J, Nguyen T, Law AV, Hodding J. Adverse drug reaction among children over a 10-yearperiod. Pediatrics. 2006;118:555-562.