- Clinical Technology

- Adult Immunization

- Hepatology

- Pediatric Immunization

- Screening

- Psychiatry

- Allergy

- Women's Health

- Cardiology

- Pediatrics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology

- Pain Management

- Gastroenterology

- Infectious Disease

- Obesity Medicine

- Rheumatology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Pulmonology

Crohn Disease and Smoking: Is it Ever Too Late to Quit?

Crohn disease-its development, flares, progression, need for drug therapy, and need for surgery-is affected by cigarette use.

Short answer: no.

Despite the fact that this study didn’t produce overwhelming numbers, its results suggest that it’s never too late to quit smoking-like cardiovascular and pulmonary patients, Crohn disease (CD) patients will have better outcomes even if they quit smoking late in the course of their disease.

Previous research has shown that smoking is a risk factor for the initial development of CD, for disease flares once CD has been diagnosed, for disease progression, for the need for corticosteroids and immunosuppressives, and for the need for surgery. But prior studies have not looked at whether quitting reduces these risks, and how the timing of quitting affects outcome.

Those variables are addressed in this retrospective, multicenter study of 1115 CD patients from Australia and New Zealand. Study patients had a minimum disease duration of 5 years by the end of the analysis period (mean disease duration was more than 16 years). Patient self-report was used to determine smoking status (start/stop dates, average number of cigarettes per day); number, dates, and types of CD-related abdominal surgeries; family history and medication use; and, disease behavior at time of diagnosis and at follow-up (B1-inflammatory, B2-stricturing, or B3-perforating).

Positive smoking status was defined as having smoked at least 1 cigarette a day for a minimum of 3 months; ex-smoking status required at least 3 months smoke-free. “Ever-smokers” were defined as ex-smokers or current smokers. Life-long non-smokers were defined as those who had never regularly smoked 1 or more cigarettes per day and had not smoked 100 cigarettes in their life.

More smokers had a second surgical resection than patients who quit at or before their first resection and non-smokers; with a 40% increase in surgical rate (P = .044). The effect on first surgeries was less pronounced (20% increase, without statistical significance).

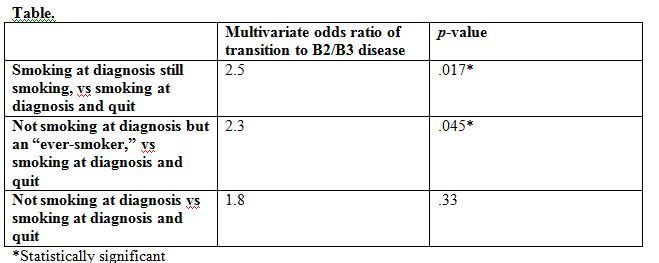

Controlling for disease-specific factors (severity, disease duration, terminal ileal and perianal disease, use of immunosuppressive agents or intravenous steroids), self-reported smoking behavior increased the risk of transition from B1 disease to B2 or B3. Three comparison groups were identified; the multivariate odds ratio quantifies the elevated risk of transition in the specified smoking cohort. (Table)

The study demonstrated some effect from cigarette dose (based on self-reported cigarettes per week). The odds of transition double when number of cigarettes smoked increase from 1 to 5 per week to 6 or more, and then nearly quadruple at 20 per week, but statistical significance isn’t reached until the 20-cigarette threshold is met. Less impressive numbers were seen for dose-effect on the risk of surgery occurrence-although the study demonstrated 30% increases in first surgery, second surgery occurrence risk did not consistently increase with cigarette weekly dose, and statistical significance was not seen for surgical risk.

This is a study that becomes less impressive when you read beyond the abstract. Despite a fairly large cohort, many of the observed effects did not reach statistical significance-one only learns this through a careful read of the whole paper.

But even after recognizing the inaccuracy of this data set (all self-report), we’re left with a clear mandate to recommend smoking cessation to all CD patients. This is the kind of suggestive study that should be replicated prospectively, and with a more accurate data source such as chart review or electronic health record extraction.

Reference:

Lawrance IC, Murray K, Batman B, et al. Crohn’s disease and smoking: is it ever too late to quit?

J Crohns Colitis. 2013 (June). Published online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.crohns.2013.05.007

Clinical Tips for Using Antibiotics and Corticosteroids in IBD

January 5th 2013The goals of therapy for patients with inflammatory bowel disorder include inducing and maintaining a steroid-free remission, preventing and treating the complications of the disease, minimizing treatment toxicity, achieving mucosal healing, and enhancing quality of life.