- Clinical Technology

- Adult Immunization

- Hepatology

- Pediatric Immunization

- Screening

- Psychiatry

- Allergy

- Women's Health

- Cardiology

- Pediatrics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology

- Pain Management

- Gastroenterology

- Infectious Disease

- Obesity Medicine

- Rheumatology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Pulmonology

"Club" Drugs 101: Substance Use and Abuse for 21st Century Clinicians

Over the past 5 to 10 years, there has been an increasing incidence of synthetic club drug use that has quietly permeated the adolescent and young adult culture. This review of MDMA, also known as Ecstasy, ketamine, GHB, and methamphetamine, provides a basic introduction to help practitioners get up to speed.

Fifteen-year-old Michael has been your patient since he was born. He has always been healthy, and his annual well visits have been uneventful. Last week, you saw his 12-year-old sister and 11-year-old brother for their summer camp physical examinations. When you asked their mother how things have been going at home, she rolled her eyes and laughed. "Well, the younger kids have been doing great. Michael, on the other hand . . . let's just say he's become a challenge."

You think back to that conversation as you pick up his chart to see him today and think, "Michael is such a great kid. His mom must be exaggerating." Your jaw drops when you see him. The clean-cut kid you remember has disappeared. In his place is the new Michael-complete with a half-shaved head of green hair, multiple earrings in each ear, a small nose stud, and a stainless silver tongue ring. Michael seems to sense your surprise, smiles, and asks, "So what do you think???"

You somehow maintain your composure and proceed with the history and physical examination. Michael admits that he and his parents "haven't been seeing eye to eye recently" on a lot of issues. During the past year, he connected with a new group of friends. Saturday night movies and video games have been replaced by all-night clubs, where he dances to "trance" and "techno" music. Michael confides that he tells his parents that he sleeps at a friend's house on Saturday nights, while in reality, he stays at the clubs until 6 am every Sunday morning.

This gives you a perfect opportunity to ask Michael about alcohol and marijuana use. Michael laughs and answers, "No way! When I party the only thing I drink is bottled water. Alcohol and weed wear ya out. I don't do any dangerous drugs like cocaine, LSD, crack, or heroin. But I sometimes need a little something to keep me going until Sunday morning. . . ."

When you ask for clarification, Michael shakes his head and slyly says, "If you gotta ask then you just don't get it. . . ."

Like Michael, most teenagers correctly assume that their health care providers are relatively uninformed when it comes to the new generation of substance abuse. However, teenagers of all socioeconomic backgrounds have demonstrated an increase in experimentation and use of various synthetic substances designed to enhance their overall experience when attending a party known as a "rave."

A rave is an all-night dance party-usually held at a large dance club or at a rented venue (such as a warehouse). These parties attract hundreds to thousands of participants and often include special effects with lighting, lasers, smoke, professional dancers, confetti, etc. Most commonly, the DJ fills the room with trance music-so named for its unending repetition of musical phrases and rhythms.

A significant part of "rave culture" involves the availability of, and subsequent experimentation with, synthetic drugs designed to augment the trance music and the visual stimulation provided by the club.

Here I describe 4 substances that are commonly abused by teenagers as part of the rave scene: 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, also known as "Ecstasy"), ketamine, γ-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), and methamphetamine. This review is meant to be a basic introduction to help practitioners get "up to speed" (forgive the pun) on these substances so that they can better communicate the risks involved to their adolescent patients.

MDMA (ECSTASY)

MDMA is an amphetamine that acts both as a CNS stimulant and as a mild hallucinogen. It is sold on the street or in clubs as Ecstasy and may also be known by its various nicknames: "E," "X," "XTC," "Love," or "Hug Drug." Although the drug has been labeled a category 1 (illegal) drug since the 1980s, it is commonly imported from the Netherlands and Belgium, and there have been reports of increasing home production in the United States.

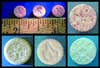

Ecstasy is generally sold as a pill inscribed with its maker's "brand name" (Figure 1). The tablets rarely contain pure MDMA and, like many illegal substances, they can be infused with other drugs (eg, caffeine, dextromethorphan, ephedrine, and methamphetamine) to enhance their effects. The Monitoring the Future Survey of 10th- and 12th-graders indicated that Ecstasy use dropped between 2001 and 2004 but that the lifetime prevalence of MDMA use among 12th-graders is still significant at 7.5%.1

Once Ecstasy is ingested, the brain undergoes an increase in dopaminergic, serotonergic, and norepinephrine pathway stimulation. Physically, this initially manifests as tachycardia, increased blood pressure, hyperthermia, bruxism (jaw clenching), and blurred vision. An hour after ingestion, most unpleasant effects are replaced by a sense of euphoria that can last for 3 to 4 hours. A hallmark of Ecstasy use is a profound feeling of "connectedness" with people: this is obviously a very attractive quality for a teenager who might be feeling detached from society or from a peer group.

Users of Ecstasy also report enhanced tactile sensations. More than one of my patients has told me: "I just love the feeling of being touched while I'm on E." Interestingly, while one might assume that this quality might lead to increased sexual activity, the sympathetic action of MDMA reportedly precludes any erectile response leading to such activity.

Many adolescents are under the mistaken impression that MDMA is safe. It is our responsibility to explain the risks. MDMA causes hyperthermia, with temperatures that often exceed 40.5°C (105°F). Accordingly, rave clubs typically provide air-conditioned spaces in which users are expected to "cool down" when not dancing. In addition, MDMA users will often consume large amounts of ice water to lower their body temperature as much as possible (remember Michael's use of bottled water?). Persons who take Ecstasy water-load while under the drug's influence, which can result in dilutional hyponatremia. It is not uncommon for Ecstasy users to present in status epilepticus because of the profound hyponatremia caused by the combination of water-loading and the salt loss from sweating.

Other risks involved with Ecstasy ingestion are arrhythmias and hepatotoxicity. In addition, the drug can cause profound hypoglycemia, which is why many users at a rave will be seen sucking on lollipops (which also helps with the bruxism).

Over the past 5 years, data have emerged suggesting that Ecstasy-even when used sparingly-can have long-term neurologic consequences. The acute increase in serotonergic activity is later replaced by a lack of serotonin in the synapses. Obviously, any patient who is sensitive to deceased serotonin levels (especially those with depression, anxiety, or any serotonin-based psychiatric condition) must be counseled against use of this drug: a post-use dysphoria can ensue that may last weeks to months before the serotonin in the brain is replenished. Even those who have used Ecstasy for short periods have demonstrated a "pruning" of serotonergic axons and terminals that subsequently affects the brain's ability to perform complex thought and higher-function processes.

Finally, be sure to inform adolescent patients of recent data suggesting that Ecstasy use can result in a frequency-dependent memory reduction. This effect appears to persist for years after use of the drug is discontinued.1-3

KETAMINE

Ketamine (also known as "K," "Vitamin K," and "Special K") was originally developed as an anesthetic, and it is still used for short-term, airway-preserving procedures in children and animals. (In fact, the substance is most commonly stolen from veterinarians' offices.) The drug is manufactured as a powder that is snorted, ingested, or even smoked. It acts as a hallucinogen when used as a club drug (Figure 2). Although its use is not as prevalent as that of MDMA or GHB, self-reports of ketamine abuse have increased over the past 6 years, and more than half of emergency department (ED) visits for ketamine ingestion involve adolescents and young adults.

In a rave setting, ketamine produces a dissociative effect in which the user may report an "out-of-body" experience with distorted perceptions of time and space. The effects typically begin within 30 minutes of exposure and last for approximately 2 hours. Patients who have used ketamine occasionally present with anxiety, agitation, paranoia, and vomiting. Higher doses can cause lethal respiratory depression.

The diagnosis of ketamine abuse is a clinical one because the metabolites do not appear on routine toxicology screens. Rarely, the drug can cause cardiac ischemia (from increased heart rate and blood pressure) or rhabdomyolysis. When you suspect ketamine abuse in a patient who complains of chest pain or myalgias, obtain measurements of electrolytes and levels of creatine phosphokinase and troponin to rule out a significant pathologic process.

Anecdotally, I have had teenage patients insist that ketamine is not dangerous because it is "a medical drug." One of the challenges of working with adolescents is explaining that a medical drug, if used incorrectly, can have profound short- and long-term consequences. Repeated ketamine use can be addictive, and even a single use can occasionally produce audiovisual "flashbacks" (similar to those described by phencyclidine [PCP] users). In addition, case reports have suggested that long-term memory deficits can occur with long-term nonmedical use of ketamine.

GHB

Until 1990, GHB was sold in health food stores for its muscle-building (through growth-hormone stimulation) and alleged fat-burning properties. The FDA then outlawed the substance because of its euphoric and nervous systemdepressant effects. Unfortunately, its precursor molecule, 1,4-butanediol, continues to be sold as a nutritional supplement that can be converted to GHB in vivo. On the street, the drug is known as "G," "GHB," and "Georgia Home Boy" (among other names). The drug is produced in the United States, Mexico, and throughout Europe and is purchased in small vials of liquid that can be taken directly or added to beverages.

Once taken, the drug crosses the blood-brain barrier and acts as a CNS sedative while producing feelings of euphoria and heightened sexuality. Indeed, over the past few years, GHB has made the news because of its amnesic properties as a "date rape" drug, similar to the benzodiazepine flunitrazepam (Rohypnol). Alcohol tends to enhance both the desired and adverse effects of GHB. Overdoses are fairly common because the exact concentration in each GHB vial is often unknown (Figure 3). At higher doses, the drug causes hypersalivation, hypotonia, and obtundation that may progress to coma with or without respiratory depression.

GHB is addictive. Adolescents who attempt to quit may experience significant withdrawal symptoms, including anxiety, tremors, and insomnia. Most of these symptoms tend to decrease within 1 to 2 weeks of cessation. However, GHB withdrawal leading to psychosis (that can last for weeks to months) has been reported.

It is important to counsel your adolescent patients that GHB is dangerous, even though it was once legally sold in the United States.

METHAMPHETAMINE

Use of this highly addictive stimulant has become epidemic among adolescents and young adults over the past decade. The drug, which can be ingested, smoked, or injected, is easy to synthesize. On the street, the substance is known by various names, including "Tina," "Crystal Meth," "Crystal," and "Ice" (Figure 4). The Monitoring the Future Survey estimates that 6.2% of high school seniors admit to using this drug at least once.3

Methamphetamine acts as a CNS stimulant. It causes the release of large amounts of dopamine, which creates the sensation of euphoria, increased self-esteem, and alertness. Users also report a marked increase in sexual appetite, which often leads to significantly risky sexual behaviors while under the drug's influence. In large enough doses, methamphetamine can produce psychosis. Roughly 60% of users who present to the ED have documented mental status changes. These mental status changes may abate with quiet isolation, but haloperidol or diazepam may be needed if agitation becomes severe.

Initially, methamphetamine can increase heart rate and blood pressure simultaneously. Consequently, the user may present with anxiety or palpitations. As with ketamine, complaints of chest pain should prompt an appropriate cardiac workup because the drug can be cardiotoxic. Similarly, any focal neurologic complaint warrants evaluation for a cerebrovascular accident. Patients may also present with acute respiratory distress (when the substance is smoked) secondary to inhalation injury or pulmonary edema.

When you counsel teenage patients or young adults about methamphetamine, emphasize the profoundly addictive nature of the drug. As with cocaine, coming off of methamphetamine causes an intense dysphoria, which prompts the user to seek out more of the drug to treat the dysphoric feelings. Even a handful of "tries" can lead to a powerful emotional addiction. Treatment usually requires the intervention of the patient's family as well as a substance abuse specialist team experienced in treating methamphetamine addiction.

CONCLUSION

An important milestone in an adolescent's development is the formation of a secondary family consisting of his or her peer group. It is normal for the adolescent to try new activities and social roles with this peer group. When the group brings the teenager into the world of substance abuse, it is often quite difficult for him or her to risk rejection from the secondary family by refusing to partake in this "bonding" activity.

Health care providers have an important role in helping the adolescent understand the risks involved with drug experimentation. The clinician may not be able to convince a teenager not to experiment, but he or she can provide information about these substances that will help the adolescent make the best choices possible. However, this information cannot be transmitted unless the provider has a fundamental understanding of exactly what substance (or substances) the teen is using-and knowledge of why that drug (or drugs) is (are) dangerous.

As I mentioned, this article is designed to be an introduction to club drug use during adolescence. I encourage you and your patients to visit the Web sites cited in the Box to further familiarize yourself with these issues and substances.

References:

REFERENCES:

1.

Morgan MJ. Memory deficits associated with recreational use of "ecstasy" (MDMA).

Psychopharmacology.

1999;141:30-36.

2.

Zakzanis KK, Young DA. Memory impairment in abstinent MDMA ("Ecstasy") users: a longitundinal investigation.

Neurology.

2001;56:966-969.

3.

National Institue on Drug Abuse. Overall teen drug use continues gradual decline; but use of inhalants rises. Available at:

http://www.nida.nih.gov/Newsroom/04/2004MTFDrug.pdf

. Accessed April 5, 2005.