- Clinical Technology

- Adult Immunization

- Hepatology

- Pediatric Immunization

- Screening

- Psychiatry

- Allergy

- Women's Health

- Cardiology

- Pediatrics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology

- Pain Management

- Gastroenterology

- Infectious Disease

- Obesity Medicine

- Rheumatology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Pulmonology

A Case of Worsening Dyspnea and Cough

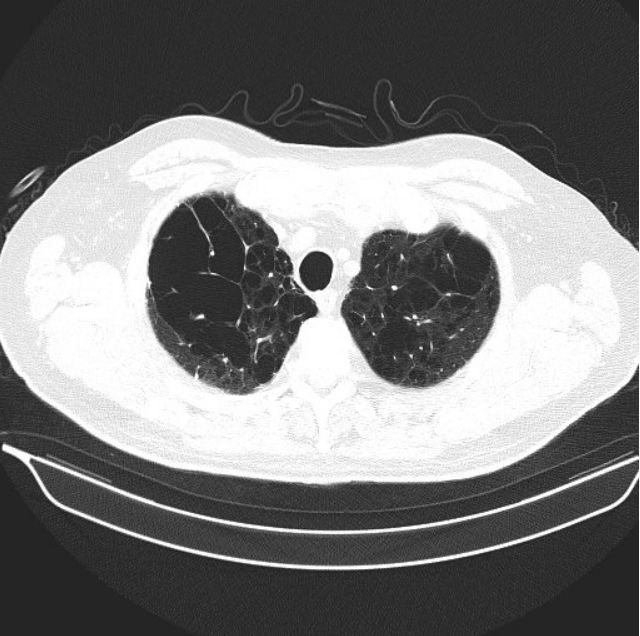

Figure 1.

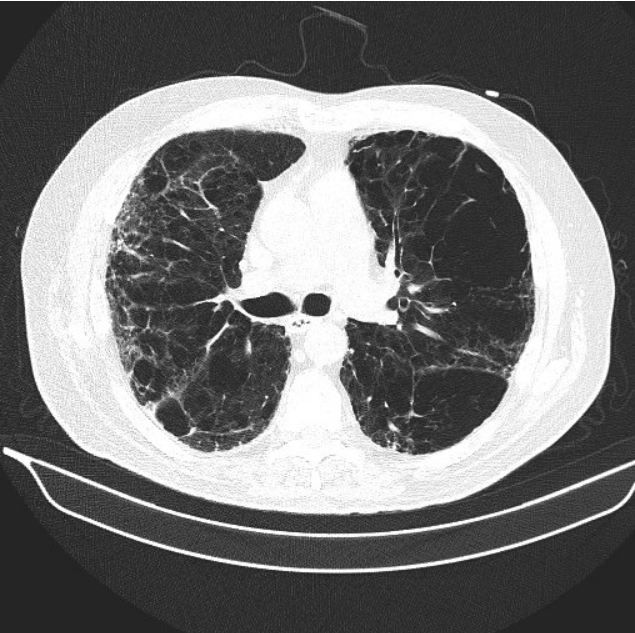

Figure 2.

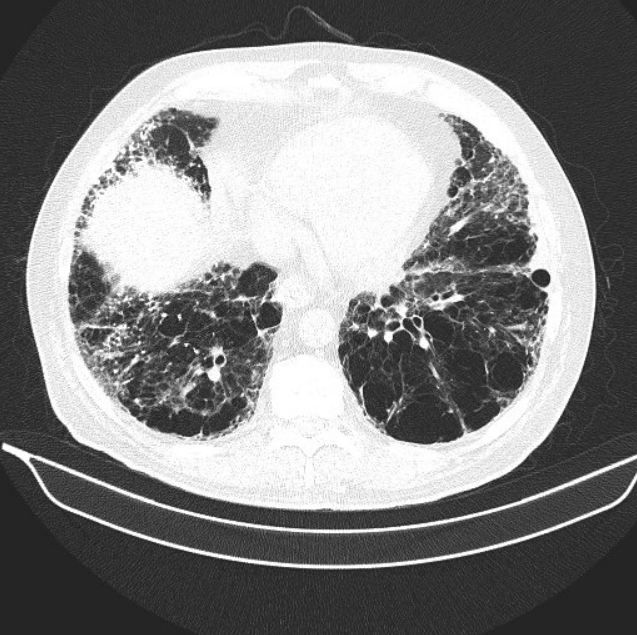

Figure 3.

Bob is a 72-year-old male, with a 40-pack-year smoking history. He quit about 8 years ago, when severe COPD was diagnosed. Until last year, he had been stable on his regimen of Advair 250/50 and Spiriva Handihaler, other than an occasional “bronchitis,” usually treated with an antibiotic and/or steroids. Over the past year or so, however, he has noticed a marked turn for the worse. He no longer can walk up the steps in his house without stopping and gasping for breath. He also notes that getting the paper in the morning from the driveway has become a chore, particularly when he bends over. His cough has gotten markedly worse, and is described as hacking and nonproductive.

1. What could be causing the subacute worsening of Bob’s symptoms?

The differential is large, as almost all pulmonary and many non-pulmonary diseases present with the insidious onset of dyspnea and cough. The important teaching point is that patients with COPD, particularly those who had a relatively stable course, may have other etiologies for worsening symptoms than just progression of their COPD. A good clinician will delve into the history more to find a clue.

Bob denies taking up tobacco again. He denies any chest pain. He recently had a cardiac stress test and echocardiogram and was told that the results were unremarkable. He denies any new hobbies or pets. He has travelled to Florida and Europe over the past 2 years. Most of his leisure time now is spent watching television or reading in the house. He denies any new symptoms of arthritis. He notes no mold problems in the home.

Physical Exam:

Temp: 98.6 Pulse: 89 RR: 20 BP: 135/85 O2: 94%

General Appearance: Slightly anxious male, mild respiratory distress

HEENT: Normal

Skin: Numerous actinic keratosis, age-related changes

Lungs: Decreased breath sounds, prolonged expiratory phase, crackles at bases

Heart: S1, S2, no murmurs, rubs, gallops

Abdomen: Normal

Extremities: Normal pulses, +clubbing, no cyanosis, edema

Neuro: Grossly intact

Please click below for next question and discussion.

2. What are the abnormal findings so far? Does this help us narrow the differential? What should be done next?

Abnormal findings include the low oxygen saturation, abnormal pulmonary exam including “crackles,” and clubbing noticed in the extremities. Although low oxygen saturation is common in COPD, crackles and clubbing are not signs of this disease. Clubbing can be seen in a number of chronic pulmonary and extrapulmonary diseases-including pulmonary malignancy, interstitial lung disease, bronchiectasis, and inflammatory bowel disease. Probably the most common causes of crackles in the lung acutely are infectious; in a chronic setting, however, crackles should clue you into the possibility congestive heart failure or an interstitial lung disease.

The primary care physician was concerned about the possibility of interstitial lung disease or pulmonary malignancy. He sent the patient for a high resolution CT of the chest (Figures 1-3; please click figures to enlarge) as well as pulmonary function testing (Table, see next page).

Please click below for Table, Interpretation, Clinical Course, and Diagnosis

Table. Results of pulmonary function testing

Interpretation

Flows show evidence of moderate obstruction. Lung volumes are normal. Diffusing capacity is very severely reduced. These PFTs, in the absence of additional clinical information, might be interpreted as consistent with COPD. However, the marked reduction of DLCO-which is way out of proportion to the reduction in flows, should clue the clinician into the possibility of a mixed defect. In this patient both the severe emphysema and the pulmonary fibrosis seen on CT scan are negatively affecting the lung’s ability to diffuse CO into the bloodstream, which accounts for the very severe reduction in diffusing capacity. Interestingly, fibrosis and COPD actually counteract each other in flows and volume. Pulmonary fibrosis will actually increase the FEV1/FVC ratio, and COPD will reduce it. Alternatively, pulmonary fibrosis typically reduces lung volumes symmetrically, while COPD can raise TLC and FRC due to hyperinflation. Thus, when patients have combined pulmonary fibrosis and COPD, often lung volumes and flows are relatively preserved, and diffusing capacity is markedly decreased, as seen in this patient.

Clinical Course

The primary care doctor made a tentative diagnosis of pulmonary fibrosis, and referred the patient to a pulmonologist with a special interest in interstitial lung disease. The pulmonologist confirmed the history, and obtained a careful occupational history, toxic drug or exposure history, and sent off screening labs for collagen vascular disease and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. These were essentially negative, other than an ANA that was mildly elevated at 1:40 with a speckled pattern. The patient was discussed in a multidisciplinary conference that included a radiologist, pulmonologists, rheumatologist, and pathologist.

Bob was given the diagnosis of idiopathicpulmonaryfibrosis.

He was enrolled in a pulmonary rehabilitation program. During his screening 6-minute walk, and also during exercise at rehabilitation, he was noted to have severe oxygen desaturation during exercise to 74%. A portable oxygen concentrator to use at night and with exercise was obtained. Bob was also started on nintedanib, after a careful discussion of the risks/benefits of treatment and alternatives. Over the past 6 months, Bob feels that his symptoms have not significantly changed one way or another. He has had mild diarrhea since starting on nintedanib, but he is able to control it well with occasional use of OTC loperamide.

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

IPF is a devastating disease of the lung, causing progressive fibrosis that leads to worsening dyspnea and cough over time. The course can be unpredictable and variable in an individual patient, but on average, patients die from this disease within 3 years of diagnosis. Exacerbations can occur at any time and are particularly ominous, often leading to death within a few months. The disease is predominantly one of the elderly, and men are affected more than women. The cause is unknown, but it is important to rule out other causes of interstitial lung disease, such as collagen vascular disease, medications or toxins, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

Exacerbations can occur at any time and are particularly ominous, often leading to death within a few months.

Until recently, treatment had been largely supportive. However, in 2015, 2 medications were approved for the treatment of this disease in the United States: pirfenidone and nintedanib. Both medications have been shown to slow the progression of this disease in half, on average. Many trials for new medications are presently underway. Thus, the outlook for treatment and prognosis for this disease is improving, and early diagnosis and referral to an appropriate specialist is important. Many patients like Bob have symptoms for many years before IPF is diagnosed, often in its late stages. Careful attention to patients’ symptoms, physical exam, labs, and radiological studies may help clinicians diagnose this disease earlier and improve the prognosis.

References:

. Collard HR, Ryerson CJ, Corte TJ, et al. Acute Exacerbation of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An International Working Group Report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(3):265-275.

. Ley B, Collard HR, King TE Jr. Clinical course and prediction of survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(4):431-440.

. Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(6):788-824.