- Clinical Technology

- Adult Immunization

- Hepatology

- Pediatric Immunization

- Screening

- Psychiatry

- Allergy

- Women's Health

- Cardiology

- Pediatrics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology

- Pain Management

- Gastroenterology

- Infectious Disease

- Obesity Medicine

- Rheumatology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Pulmonology

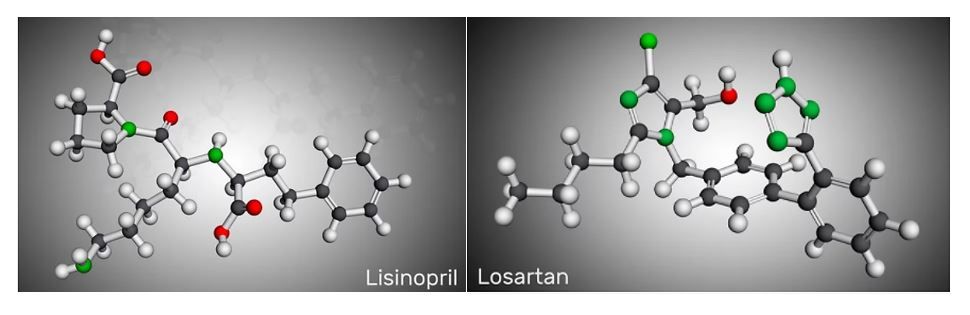

ACEIs, ARBS Equally Effective First-line Hypertension Rx but ACEIs Have Better Safety Profile

A head-to-head study found the 2 drug classes equally effective first-line therapies but ARBs, though prescribed less often, proved somewhat safer.

CLINICAL FOCUS: PREVENTIVE CARDIOLOGY

©bacsica/stock.adobe.com

Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors were found equally effective for first-line treatment of hypertension in a large multinational retrospective cohort study published online July 26, 2021, in the journal Hypertension.

The traditional antihypertension agents differed, however, in terms of adverse effects with ARBs demonstrating a more favorable safety profile vs ACEIs.

"Physicians in the United States and Europe overwhelmingly prescribe ACE inhibitors, simply because the drugs have been around longer and tend to be less expensive than ARBs," said George Hripcsak, MD, the Vivian Beaumont Allen Professor and chair of biomedical informatics at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and senior author of the study in a Columbia University statement. "But our study shows that ARBs are associated with fewer side effects than ACE inhibitors.”

"US and European hypertension guidelines list 30 medications from 5 different drug classes as possible choices," added Hripcsak, "yet there are very few head-to-head studies to help physicians determine which ones are better."

The paucity of those head-to-head studies, the authors write, was the impetus for the current study which focused on first-time users of ACEIs and ARBs and culled real-world data from electronic health records of approximately 3 million patients in the US, German, and South Korea, held in 8 large databases.

For study inclusion, patients were required to have initiated treatment for hypertension with ACEI or ARB monotherapy between 1996 and 2018.

To mimic enrollment in a prospective study, investigators estimated hazard ratios using techniques to minimize both residual confounding as well as bias (ie, large-scale propensity score adjustment, empirical calibration, and full transparency).

The primary outcomes of interest were included acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure (HF), stroke, and composite cardiovascular events (CVEs). The team also analyzed a wide range (51) of secondary and safety outcomes including angioedema, cough, syncope, and electrolyte abnormalities.

On analysis of the 8 databases, Hripcsak and colleagues found ACE inhibitors were far more frequently prescribed as initial hypertension treatment (2 297 881 patients) than were ARBs (673 938).

“We found no statistically significant differences between patients on ACE inhibitors and patients on ARBs for risk of the primary outcomes of AMI (HR, 1.11 [95% CI, 0.95-1.32]), HF (HR, 1.03 [95% CI, 0.87-1.24]), stroke (HR, 1.07 [95% CI, 0.91-1.27]), or composite CVEs (HR, 1.06 [95% CI, 0.90-1.25]),” the authors reported.

In the secondary and safety outcome analysis ACE inhibitors were associated with a significantly increased risk of angioedema (HR, 3.31; 95% CI, 2.55-4.51; P <.01), cough (HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.11-1.59; P <.01), acute pancreatitis (HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.04-1.70; P =.02), and gastrointestinal bleeding (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.01-1.41; P =.04) vs ARBs.

“Despite being equally guideline-recommended first-line therapies for hypertension, these results support preferentially starting ARBs rather than ACE inhibitors when initiating treatment for hypertension for physicians and patients considering renin-angiotensin system inhibition,” the authors concluded.

Among the study limitations noted in the publication authors emphasized variations in follow-up time and medication choice.

The ACE inhibitor used most frequently was lisinopril (80%) and the ARB, losartan (45%).

The authors also point out that further study is warranted to test for potential heterogeneity at the level of specific drugs and they caution that the results seen with monotherapy in the study may not generalize to patients prescribed multidrug therapy at treatment initiation.